The Covid-19 crisis has renewed interest in the merits of introducing a tax on net wealth in the UK. A key issue to consider is whether such a tax should be operated uniformly across the country or with some elements devolved to the governments in Edinburgh, Cardiff and Belfast.

There has been significant recent interest in the idea of establishing a broad-based UK tax on the ownership of most (or all) types of asset, net of any debt – see, for example, the report and associated papers of the Wealth Tax Commission.

Some aspects of such a wealth tax are conducive to being devolved. But devolving autonomy for aspects of a wealth tax would also bring a number of challenges over and above those posed by income tax (which is partially devolved in Scotland and Wales).

Whether the potential benefits of wealth tax devolution would be seen to outweigh the costs remains an open question – and would depend to a significant extent on aspects of tax design and implementation at the UK level.

Why devolve powers over taxation?

At the outset, it is worth reminding ourselves why we might want to devolve powers over tax in the first place – and equally, why we might be reticent about doing so.

Devolving control over aspects of tax can potentially improve outcomes in various ways. It allows policy to respond to different needs or preferences in a devolved territory, and enhances the financial accountability of devolved governments for its policy decisions.

But tax devolution can also bring costs or risks. These include diseconomies of scale in collecting or administering tax, downward competition over tax rates to compete for mobile tax bases, and inequalities in public services provision across the UK – if there is significant variation in the size of the tax base in different jurisdictions.

The challenge is to identify taxes, and a set of rules within which they can operate, that deliver these benefits while minimising the risks or costs.

Which tax powers are currently devolved?

Until recently, the UK’s devolved governments in Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland had only limited powers over tax – amounting to control over council tax and non-domestic rates. In recent years, a fairly extensive programme of tax devolution has been underway in Scotland and Wales. Income tax has been devolved to varying degrees, as well as landfill tax and stamp duty on property transactions. In Northern Ireland, there were plans partially to devolve corporation tax, although these have now been dropped.

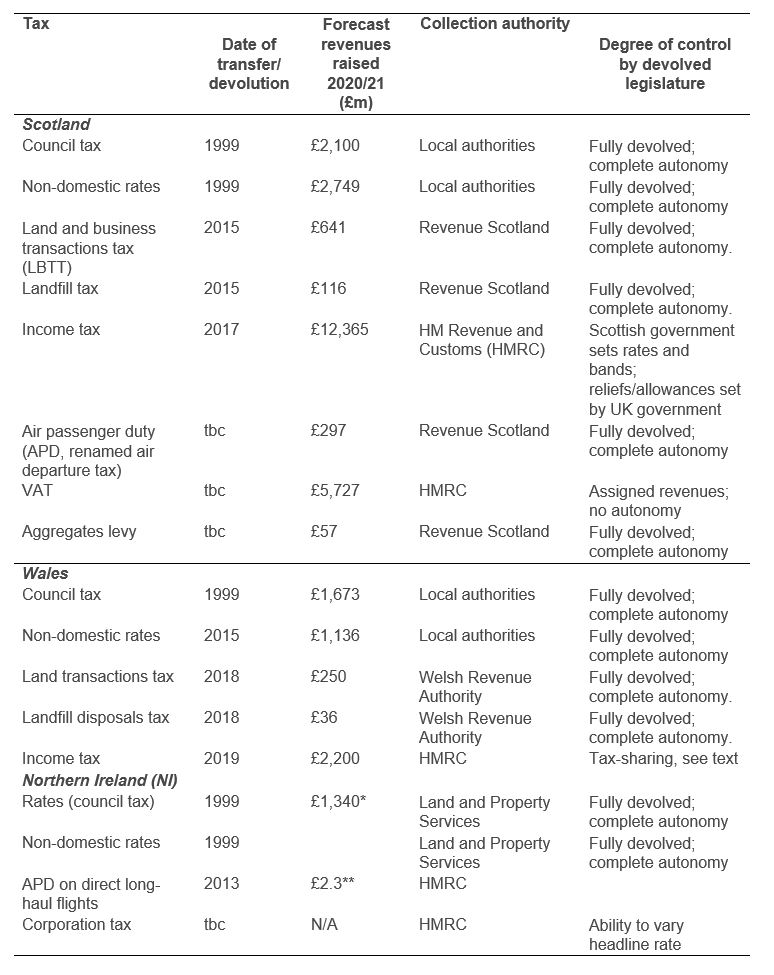

Table 1 summarises devolved taxation arrangements in Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland. Further details are set out in Eiser (2020).

Table 1: Devolved and assigned revenues in Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland

Notes: * This figure of £1.34 billion is the sum of forecast domestic and non-domestic rates revenues for both the district councils and the NI Executive (rates revenues are shared across both tiers of government) **This is the cost of the policy decision to zero-rate long haul flights in 2020/21, which is reimbursed to HM Treasury from the NI Executive.

Would a wealth tax be suitable for devolution?

In thinking about whether a wealth tax might be suitable for devolution, factors we might want to take into consideration include:

- Whether the tax could be operated efficiently at devolved level.

- How mobile the tax base might be across the UK in response to differences in tax policy.

- Whether there is any evidence for differences in preferences for wealth taxation in different parts of the UK.

- The extent to which those liable for the devolved tax are also beneficiaries of devolved government spending.

- The ‘visibility’ of the tax for those who are liable.

So how does a wealth tax stack up?

The answer depends to a significant extent on the way that a wealth tax is configured at the UK level in the first place. A narrow tax on the ‘super wealthy’ (that is, one with a high exempt amount) would be less suitable for devolution than a broader tax, given considerations around the mobility of the base, and the objective of tax devolution to enhance accountability by giving a significant section of the electorate a stake in the policies of the devolved government.

There are some features of a wealth tax that may make it suitable to devolution. Assuming it would be paid through self-assessment, it would be very visible (that is, taxpayers would have a good idea what their liability was, unlike with, say, fuel or alcohol duties). And assuming that liability was based on residence, there would be a linkage between the liability for a devolved tax and the benefit from devolved government expenditure (unlike with, say, corporation tax).

It’s not really clear that preferences for a wealth tax differ in Scotland (or any other devolved nation) relative to England. But there is evidence that Scottish and Welsh taxpayers would generally prefer new taxes to be levied at a devolved level.

But there are three areas where devolving a wealth tax might create particular challenges: administrative issues; the scope for behavioural responses; and the uneven distribution of wealth across the UK.

How straightforward would it be to identify the geographical location of the people or assets liable for a wealth tax?

For a wealth tax to work effectively at devolved level, there would need to be clear rules about who or what is subject to the tax (the tax base), and how the geographical location of those people or assets is defined.

Assuming the tax unit for the wealth tax was the individual (as opposed to the family), then existing rules of HM Revenue and Customs (HMRC) for identifying Scottish and Welsh taxpayers for income tax purposes could be used to determine taxpayer status for a devolved wealth tax, and adopted for Northern Ireland as required.

The lessons so far from the Scottish income tax experience have been that identifying ‘Scottish’ taxpayers is not entirely problem-free. It can be difficult for HMRC to know when a taxpayer has moved – and further problems emerge when taxpayers have more than one residence. On the other hand, it has been relatively straightforward for HMRC to operationalise a different system of rates and bands in Scotland, at fairly minimal cost.

But wealth taxation brings a number of additional challenges. First, there is a case for taxing land and property wealth on the basis of the physical location of the asset, rather than the residence of the taxpayer who owns the property. This would create an added but not insurmountable challenge.

Second, and more importantly, there is the issue of assets placed in trusts, foundations and similar vehicles. The issue of taxation of trusts is challenging at the UK level, let alone when devolution is considered. The beneficiaries are frequently either dispersed or not yet born; there is no point taxing the trustees as they can be located anywhere; and while it may be possible to tax the donor, it is not clear what happens if he/she is deceased.

Administratively, it would be simplest to tax trusts at UK rates according to UK policy, in effect removing trusts from the purview of devolved taxation. But this would be unsatisfactory to the extent that it would provide strong incentives for Scottish taxpayers to place assets into trusts if, for example, a higher rate of tax was set in Scotland. Ultimately, the ‘devolved’ solution would need to be analogous to whatever was proposed at the UK level.

How mobile might the tax base be to differential tax policy within the UK?

If the wealth tax base was highly mobile across the UK in response to differences in tax policy, this might mitigate against the idea of tax devolution: it might create incentives for governments to undercut each other on tax, ultimately benefiting nobody.

The extent to which wealth might be mobile across the UK in response to divergence in wealth tax policy is highly uncertain. The answer will be significantly dependent on issues around how the tax base is defined, as noted previously. Some degree of response is inevitable and is not necessarily problematic – the difficulties arise if taxpayers can shift the geographical status of aspects of their wealth (or themselves) relatively easily.

It is worth noting that in Switzerland and Spain – which both operate wealth taxes at a sub-national level – there is evidence of significant and material behavioural responses (see Brülhart et al, 2019 for Switzerland; and evidence in Advani and Tarrant, 2020).

If there are concerns that devolution of a wealth tax might trigger some form of downward tax competition, resulting in rates that are socially sub-optimal, one solution – at least in the short term – would be to constrain the scope of devolved powers over the setting of rates or bands. The constraining of a devolved government’s tax powers so that rates can be varied within pre-defined range is common practice in other countries.

Would devolving a wealth tax be unfair to nations where levels of wealth are lower than the national average?

Wealth is unevenly distributed across the UK. The devolved nations would be likely to raise less tax per capita from a given wealth tax than England (given the significance of wealth concentrated in London). Tying additional spending in different parts of the UK directly to revenues raised in each territory from a new wealth tax would be challenged on grounds of equity.

At face value there is a solution to this issue, and that is to follow recent arrangements for devolved income tax in Scotland and Wales. The two nations raise relatively less income tax per capita than England. The existing fiscal frameworks address this by equalising away differences in income tax capacity at the point when income tax revenues are devolved and making the Scottish and Welsh budgets liable for divergence in relative growth in revenues over time. This approach also protects the devolved budgets from UK-wide revenue shocks, such as those that occur in recessions.

But the limitation of this approach is that it implicitly assumes that it is reasonable to hold the devolved governments financially to account for differences in relative growth in wealth over time. But we know that wealth has tended to accumulate faster in parts of England than in other parts of the UK in recent years, so the devolved governments might be reluctant to sign up to a model that will disadvantage them if wealth in the devolved territories is likely to grow less quickly over time.

At the same time, this approach assumes that the UK government would be willing to transfer some of the revenues raised from a wealth tax in England to one or more of the devolved territories. Whether or not this would be deemed politically acceptable is uncertain.

Alternative models are possible. But agreeing mechanisms for adjusting the devolved governments’ block grants in such a way as to respect notions of ‘fairness’ for taxpayers in England and the devolved nations will be one of the major barriers to devolving elements of a wealth tax.

Conclusions

There is evidence of continuing demand for further tax devolution, certainly in Scotland and Wales. Some aspects of a wealth tax are conducive to it, or elements of it, being devolved.

The successful implementation of income tax-varying policy in Scotland (and income tax powers in Wales) in recent years provides a useful blueprint for the potential operation of a devolved wealth tax. In principle, by piggy-backing on existing rules for identifying Scottish/Welsh taxpayers, the devolved governments could have some autonomy for varying aspects of a wealth tax, with HMRC continuing to collect revenues through self-assessment.

But devolving autonomy for aspects of a wealth tax would also bring a number of challenges over and above those posed by income tax. These include in particular the question of the treatment of trusts and similar vehicles, and implications of the unequal distribution of the tax base for operation of the block grant.

These issues are not insurmountable but would provide additional challenges. Whether the potential benefits of wealth tax devolution would be seen to outweigh the costs remains an open question – and will depend to a significant extent on aspects of tax design and implementation at the UK level.

Where can I find out more?

- Should a UK wealth tax be devolved? David Eiser’s paper on which this piece is based.

- The UK Wealth Tax Commission: Issues in the design of wealth taxation generally.

- Will the benefits of fiscal devolution outweigh the costs? Considering Scotland’s new fiscal framework: David Eiser considers the recent experience of tax devolution to Scotland

Who are experts on this question?

- David Eiser at the University of Strathclyde is an expert on fiscal devolution in the UK.

- David Phillips at the Institute for Fiscal Studies is an expert on devolution and fiscal policy in the UK.

- Guto Ifan and Ed Poole at the Wales Governance Centre are experts on the Welsh fiscal framework.

- David Bell at the University of Stirling is an expert on the Scottish fiscal framework.

- David Heald at the University of Glasgow is an expert on tax and devolution.

Author: David Eiser