As the UK’s job furlough scheme winds down, the government has shifted towards measures to support businesses and employees in local lockdowns. But even if Covid-19 eases, policy-makers will need to retain the capacity for selective sectoral assistance – and clarity on ‘state aid’.

The Coronavirus Job Guarantee Scheme (CJRS), which was introduced in March 2020 to encourage firms to retain their employees, will end in October. The ‘job furlough’ scheme was a national general employment subsidy designed to deal with the consequences of lockdown during the Covid-19 pandemic from April to July 2020.

The government has since argued that as substantial parts of the economy were re-opening during the summer, a general subsidy of this sort should not be continued for several reasons. First, there is the financial cost of the scheme, which, although less than originally anticipated, has already added around £40 billion to government borrowing.

Second, once sectors re-opened, many jobs that continued to require substantial financial assistance were not likely to be viable in the long run. Continued subsidy of unprofitable jobs would retard the required transfer of labour towards growing sectors where labour was in demand – for example, from personal care to social care; from retail outlets to home deliveries; and from physical activities towards developments in online platforms and intangible services.

In general, whether they are caused by financial markets, energy price hikes or pandemics, crises cause shocks that may exacerbate existing trends: for example, away from shopping in large shopping centres and department stores; away from purchases of diesel-powered vehicles; or away from over-complex and centralised financial institutions. While these transitions may require temporary assistance to some people or organisations, this should not become permanent.

Economists point out that even in normal times, there is large turnover of establishments as many entrant firms grow or fail to survive; indeed, productivity growth is often attributed to this ‘survival of the fittest’. In similar vein, the stock of unemployed is not a fixed group of people (although some individuals with poor skills or health suffer long durations out of work) but reflects a constant turnover of individuals between jobs.

Moreover, the government may consider that some market activities should be able to self-adjust to the new realities – for example, the high frequency and proximity of chains of coffee and sandwich shops on adjacent sites in large cities has often been noted; the shift to home working, to local market towns and to suburbs of consumer footfall may induce a rethink by these retail chains of where their outlets are sited. The growing concentration of economic activity in the centres of large conurbations may now be at an end as workplaces and consumers become increasingly decentralised.

The logic of this approach is that government assistance in normal times should focus on financial assistance for, and subsidised retraining of, displaced workers (given the well-known externality attached to employer-provided general training), as well as support for emergent businesses, especially on the side of cheap provision of capital and infrastructural backup in information technology, telecommunications and transport links.

Government provision – such as subsidies for training, support for the self-employment - and business rates relief, all of which are continuing into 2021 – would seem to reflect this approach.

The upsurge in Covid-19 in September raises new challenges, requiring further intervention

In an optimistic frame of mind, the UK government hoped that the Covid-19 crisis would recede and normality would resume during the summer. The rise in new cases in September and the prospect of further increases in Covid-19 cases during the autumn and winter have dashed these hopes. Some lobbyists argued for a reversal of the decision to abolish the CJRS, but the government has rejected this approach since many businesses have re-opened, although some are operating on a more restricted basis.

Instead of the CJRS, the government therefore announced a new Job Support Scheme (JSS) in September 2020, intended to provided partially subsidised wages for part-time workers in similar vein to the German Kurzarbeit scheme, as a way of dealing with temporary short-time working. But this subsidy is much less generous than the CJRS and it is expected to cost considerably less over a six-month period (around £5 billion).

It is not entirely clear what sort of jobs were likely to be affected by this scheme and it would do nothing towards retaining jobs where workers have been fully laid-off. The incidence of the JSS would be highly dependent on how employers adjusted the working hours of those employees that they intend to retain.

In the first week of October, the government effectively reversed its position, by augmenting the JSS provisions with a revised job furlough scheme, albeit one that applies only to businesses in areas facing local lockdowns. For companies that faced a legal requirement to close down due to a local lockdown, such as in the hospitality sector, employees could receive two-thirds of their pay from the government up to a ceiling of £2,100 a month for so long as the local lockdown was in place. There were also increased cash grants to businesses.

This package is less generous than the original CJRS (Disney, 2020a, 2020b) and no overall prospective costs of the scheme have been given since the geographical extent of local lockdowns is essentially unknown at this point.

Unlike the national CJRS scheme, this augmentation of the JSS as a local lockdown measure raises a number of issues:

- First, with several tiers of what is defined as a ‘lockdown’ coming into operation, which lockdowns are eligible?

- Second, will local councils or mayors be involved in deciding the nature and extent of a local lockdown?

- Third, what constitutes an eligible sector? There is already confusion as to the definition of ‘hospitality’ with the government arguing that ‘restaurants’ may stay open but not, say, pubs and bars – what therefore constitutes a restaurant, café, bar and so on?

- And finally, what about any knock-on effects onto other businesses caused by city centre closures? They presumably are not covered by the scheme, although workers in such businesses may have been eligible for support under the original provisions of the JSS for part-time working.

These factors suggest that monitoring the impact of this revised JSS, especially in ensuring that eligibility conditions are satisfied, is going to require a greater administrative input and, probably, a much greater local involvement in decision-making and in overseeing the operation of the scheme than before.

Related question: How does the government's furlough scheme work?

Related question: The UK’s job furlough scheme is coming to an end: what happens next?

Longer term, is there a need for state aid?

The government is clearly hoping that by the spring of 2021, a combination of factors will ease the requirement for measures such as the JSS, business cash transfers, rates relief and so on. But this is not the end of the story, even if local lockdowns are eliminated. Alongside these short-term responses to the Covid-19 crisis, there are longer-term considerations. There are sectors of the economy which, for a variety of reasons – including strategic, level of employment, technological features and capacity for innovation – the UK may wish to retain but that face potential long-run financial problems arising from the pandemic. These include transport, especially aviation and rail, aeronautics and other technology-intensive sectors.

Hence there will undoubtedly be a need for continued, selective, intervention in parts of the economy. Selective intervention of this type is typically termed state aid. The future UK policy on state aid has been a central issue in the negotiations over the relationship between the UK and the European Union (EU) after Brexit.

Since Covid-19-related state aid is now likely to continue well into 2021, state aid issues arising from the future EU-UK arrangements directly coalesce with Covid-19-related measures. It is this relationship that underpins the rest of the discussion here.

What are state aid rules?

Unlike general taxes and subsidies, state aid operates under certain international rules, designed to prohibit what is seen as ‘unfair’ competition between countries. While selective interventions to deal with the continuing impact of Covid-19 have been treated with a degree of flexibility by international regulatory bodies, large-scale long-run interventions, such as, for example, financial support for airlines and aeronautics, might well not be looked on so favourably. The long-running dispute between Boeing and Airbus is an obvious example.

The state aid issue has therefore now come to the forefront, not just because of the question of what comes after the CJRS but also in the context of Brexit, where, as part of the negotiation of a free trade agreement with the EU, the European Commission is insistent that UK business operates a ‘level playing field’ such that state aid rules in a post-EU UK are broadly compatible with those of remaining EU members. Hence, some understanding of the EU state aid rules is necessary in order to understand what state aid is likely to be feasible in the UK during the pandemic and its aftermath.

How might UK state aid interact with EU rules?

State aid is where a public body provides selective support to an undertaking or a sector. The EU Treaty provides that state aid that could distort competition and affect trade by favouring certain undertakings or the production of goods is illegal. The EU argues that such interventions are barriers to entry, discourage innovation and distort markets.

Not unexpectedly, the EU Treaty and European Commission regulations and guidelines contain a number of exemptions to this blanket restriction. The EU is unconcerned with small amounts of state aid that will not distort competition, and the list of acceptable forms of state aid is quite lengthy, including promotion of research and development (R&D), environmental protection, access to venture capital and help for small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), as well as underlying support for public services through infrastructure such as rural transport and social housing.

It is arguable – and indeed has been argued – that these exemptions are sufficiently broad for the UK government to implement many of its cherished technology and R&D projects within the EU state aid rules.

But there are key differences between EU state aid rules and what is envisaged by the UK as a national state aid policy (although it should be noted that an expert in the area has said that the UK has not yet produced an official domestic plan as to how it proposes to operate its autonomous state aid policy – Szyszczak, 2020).

Among the key aspects of these EU exemptions are that they are agreed jointly by EU member states, and any state aid schemes not falling within the exempted categories must be approved in advance by the European Commission. The European Commission and national courts have powers to enforce the state aid rules.

One of the ironies of leaving the EU is that the UK government would be in no position to negotiate further specific exemptions within the EU Treaty and secondary law framework. There is therefore a direct conflict between the UK wishing to have an independent state aid policy and at the same time attempting to negotiate with the EU, which wishes to have a common set of state aid rules across member states and other countries with which it has close trading arrangements.

Who uses state aid in the EU?

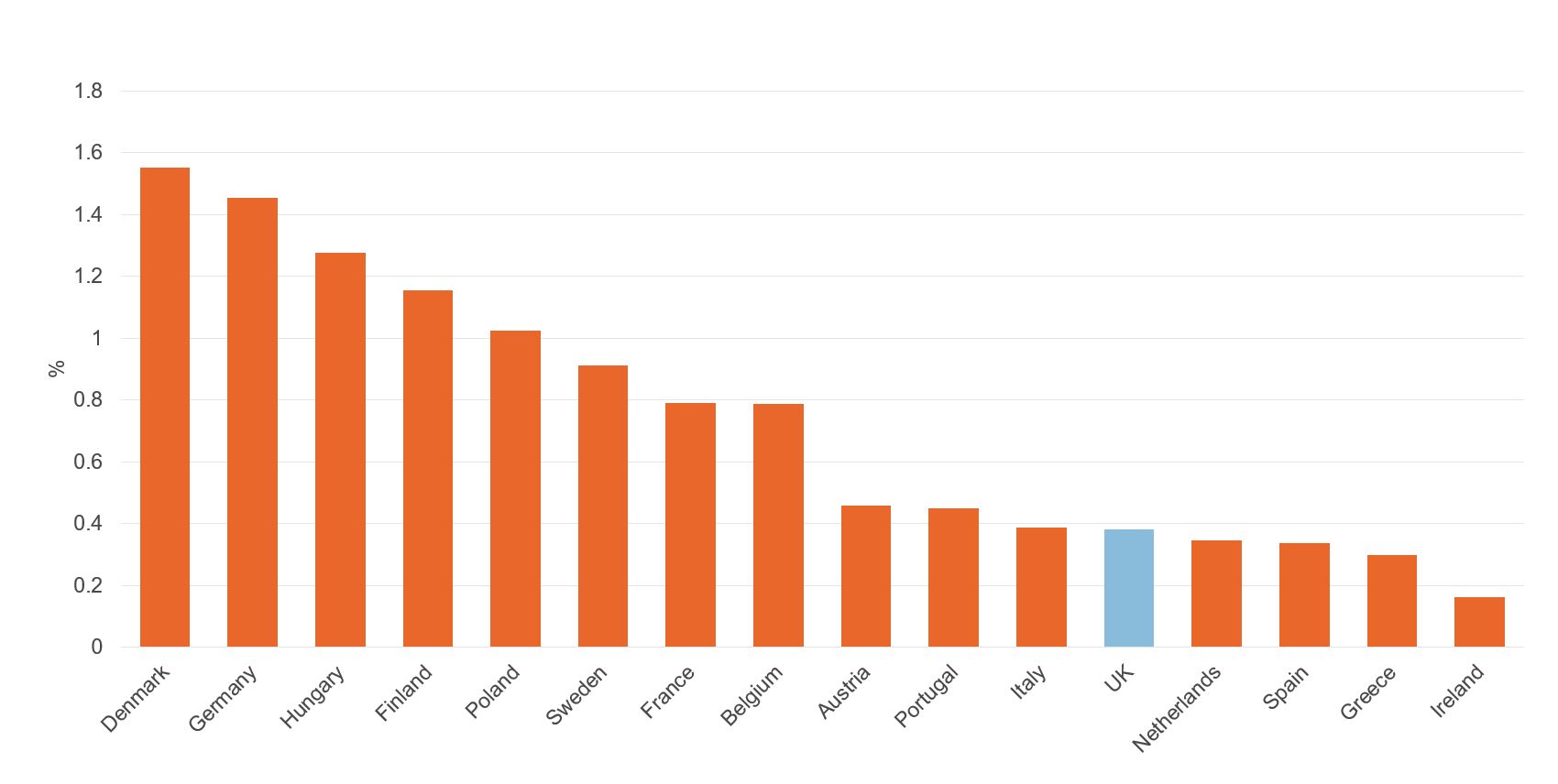

A further irony of the argument between the UK government and the EU about the application of state aid rules is that in the past the UK has used state aid only to a very limited extent. Most of the EU accession states (the formerly communist countries of Eastern Europe that joined the EU in the 2000s) use state aid to a large extent (as illustrated in Figure 1 for Hungary and Poland). But many of the long-established EU states, such as Denmark, France and Germany, also have a high proportion of GDP to state aid to selected industries and activities relative to the UK. This is despite a common set of rules being applied to all EU countries.

Figure 1: State Aid as % of GDP 2018 in current prices (selected EU countries)

How have the state aid rules been affected by Covid-19?

Early in the pandemic, the European Commission adopted a Temporary Framework in order to approve specific applications for state aid to alleviate the effects of the disruption caused by Covid-19. These approvals were wide-ranging. Not surprisingly, they included subsidies to vulnerable sectors, such as airlines in many European states including SAS, Finnair and TAP, and support for SMEs and credit markets. But they also included approval for quite loosely defined general subsidies, such as overall support for budgetary measures or for major interventions such as the UK’s job furlough scheme.

But the framework is careful to circumscribe these measures such that they are related to the original state aid rules as well as protection of existing employment levels. It is not likely that some of the more ambitious plans for state intervention that are being put forward in a post-Brexit setting by the UK’s Cabinet Office would be acceptable under this framework, even if the Covid-19 pandemic persists for a much longer period.

How does state aid fit with the rules of the World Trade Organization?

Even if the UK were to exit the EU without an agreement, it would still be party to the WTO Agreement on Subsidies and Countervailing Measures. In principle, these WTO ‘rules’ are somewhat similar to those of the EU insofar as they specify rules and broadly exempt activities.

But there are important differences: they cover only goods, not services; rules are only reactive (that is, if a complaint is made, no prior permission for a subsidy is required); they rely on state-to-state enforcement; there are no remedies for businesses or individuals that may have been disadvantaged by the illegal state aid; and there is no requirement that a business has to repay state aid that has been declared illegal.

Hence, WTO rules are perceived by the UK as giving an individual state greater flexibility in designing its own state aid regime relative to EU rules. The UK has stated that it will operate a state aid policy that is consistent with WTO rules, but it should be noted that these rules describe relations between nation states and not the domestic operation of state aid policy – for example, forms of redress for breaches of state aid rules, or a domestic regulatory environment. As mentioned above, there is not yet an official plan on how UK state aid rules would be implemented.

The uncertainty over Brexit heightens the dilemmas of Covid-19

The UK government is now moving beyond general industrial and employment support programmes such as the job furlough scheme towards selective sectoral assistance. To implement such policies, it will need to establish a clear domestic state aid policy, not least to avoid accusations of a ‘chumocracy’ and industrial support that is non-accountable.

At present, no such framework is in place. But whichever framework evolves will have to take account of the state of the Brexit negotiations, and how closely the UK is willing to align its state aid policy with that of the EU if it wishes to negotiate a free trade agreement.

Where can I find out more?

- State aid: not only about trade: UK Trade Policy Observatory briefing by Erika Szyszczak

- State aid rules and coronavirus: Summary of European Commission guidelines

- EU state aid rules and WTO subsidies agreement: Briefing paper from the House of Commons Library

- Factsheet: the Job Support Scheme: Briefing from the CBI

Who are experts on this question?

- Richard Disney, University of Sussex

- Thomas Sampson, London School of Economics

- Erika Szyszczak, University of Sussex

- Alan Winters, University of Sussex