There are growing concerns that the UK’s ethnic minorities are suffering disproportionately as a result of the pandemic – in terms of both their higher mortality risks and the worse economic outcomes for some groups.

Considerable attention has been paid to the differences in Covid-19-related mortality across ethnic groups. The disproportionate numbers of deaths particularly for some groups are stark. Research finds that relative mortality has been particularly high for black Africans, but also higher for all minority groups relative to the white UK majority, once age and location of residence are taken into account (Platt and Warwick, 2020).

These startling findings have tended to dominate discussions of ethnic inequalities associated with Covid-19 at the expense of discussions of economic effects. While this is understandable, the economic – and educational – effects deserve attention for three reasons:

- First, because they are affecting large numbers of people with potentially long-term consequences.

- Second, because loss of work or employment in a sector vulnerable to lockdown varies in its impact on other family and household members according to the ethnic group of the affected worker.

- Third, because the roots of the disproportionality in both mortality and economic effects can be largely attributed to very different distributions of ethnic groups across occupations and industries.

How is the crisis affecting different ethnic groups?

Thinking first about who is affected by the economic effects of the crisis, the implications reach across age groups – and simply in terms of numbers, the white British majority makes up four-fifths of the UK population. But ethnic groups’ shares vary across age groups.

While older people are more vulnerable to the mortality effects of Covid-19, the economic effects are likely to affect younger age groups more. Overall, around 58% of the population are working age (excluding students), a further 5% of over-16s are in education, with around 19% of the population under 16, and around 18% 65 or over.

But these patterns are very different across ethnic groups, as Figure 1 shows. Ethnic groups differ in their chances of being in work, in the shares of young populations reliant on parental incomes and in the proportions facing gaps in their education. While shares of working age are comparable for white British, Pakistanis, Bangladeshis and black Africans, the latter three groups have much higher proportions of children under 16, and of those aged 16 and over in education.

This renders them more vulnerable to effects of the crisis on education and schooling and to the challenging labour market facing those leaving education. Black Caribbeans and other white groups, meanwhile, have rather larger shares of working age than other groups.

Figure 1: Age distribution of ethnic groups in England and Wales

Source: Labour Force Survey, first quarter of 2016 to fourth quarter of 2019

Sectors and employment status

As a result of the lockdown, those working in particular sectors have been particularly likely to lose their work and livelihoods. Analysis shows that younger workers and women, as well as lower paid workers, were more likely to be working in sectors that were then shut down (Joyce and Xu, 2020). Analysis of those who have ceased paid work since the crisis confirms that women have been more affected.

Among most ethnic minority groups, however, it is men who are more likely to work in sectors that have been affected by the shutdown; and among Pakistanis and Bangladeshis, it is older rather than younger working age men. As a result, nearly 50% of Bangladeshi men work in sectors that have been affected by the shutdown, partly due to their strong concentration in the restaurants and food services sector (24% of Bangladeshi men work in these industries).

In addition to differences in the sectors in which minority men work compared with majority men, ethnic minority families may be affected by lower rates of employment among women from some groups. This makes the households in which they live potentially more vulnerable to loss of work of other household members.

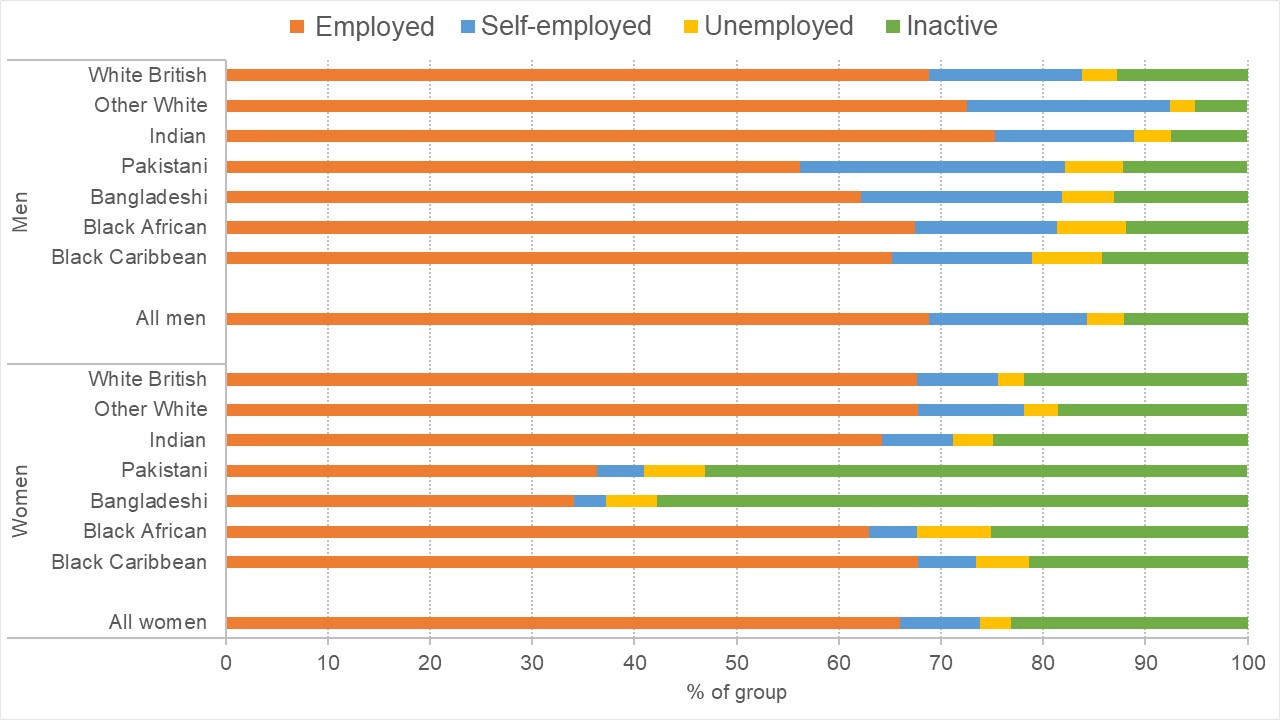

Figure 2 shows the employment status of working age men and women by ethnic group. It shows the relatively low employment (and high unemployment rates) of Pakistani and Bangladeshi women, though black African and black Caribbean women and men also face high unemployment rates.

Figure 2: Economic status among working age by ethnic group

Source: Labour Force Survey, first quarter of 2016 to fourth quarter of 2019

Figure 2 also shows variation in rates of self-employment. Analysis by the Centre for Economic Performance shows just how badly self-employed workers have been affected, with older workers and those without employees particularly hardly hit.

Rates of self-employment differ markedly across ethnic groups. While for all ethnic groups, self-employment is more common for men than women, the chances of being self-employed in the pre-crisis period were lower for Indian, black African and black Caribbean than for white British men.

But they were higher for Bangladeshi and, particularly, Pakistani men: more than one in four Pakistani men of working age were self-employed. Much of this self-employment is linked to their concentration in taxi driving: 16% of Pakistani men work in taxi or cab driving; and over one in five taxi or cab drivers is Pakistani.

Effects of the lockdown

The impact of the lockdown on workers in particular sectors also has implications for family incomes and for dependents of those workers. Loss of earnings may be cushioned when workers are living with other family members, particularly partners, also in work and in less affected sectors.

Some families are more likely to have savings that can provide some short-term insurance across loss of earnings Conversely, the loss of income may affect not only the worker but family members, where the affected worker was the main earner with multiple dependents, and where savings are limited.

The family situations of workers vary quite substantially by ethnic group. Among those working in sectors affected by the shutdown, Bangladeshi, Pakistani and black African workers have an average of 1.5 children in the household while other groups have an average of less than one child.

This suggests that child poverty, which is already higher for these groups, could increase, after having declined substantially over the early 2000s. It also raises questions about the potential educational effects on children from economically vulnerable families.

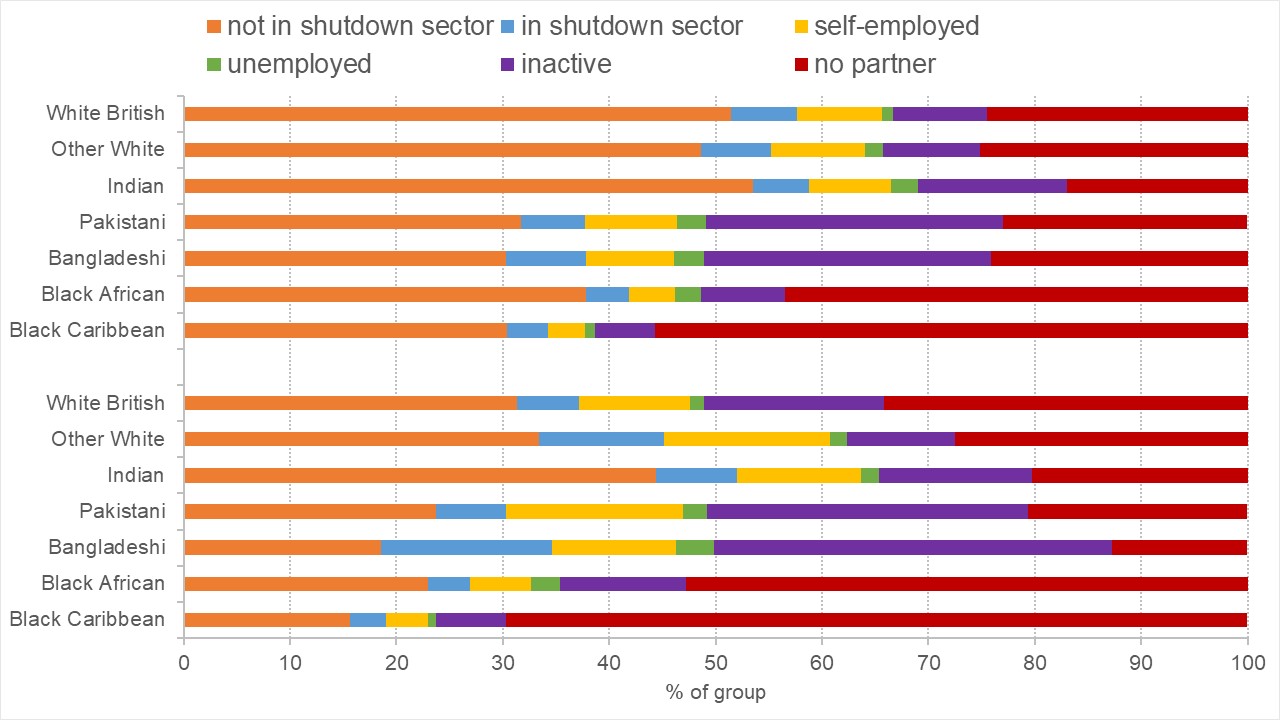

In terms of the potential resources offered by partner incomes, Figure 3 shows the economic status of partners among those either vulnerable economically (working in shutdown sectors, or self-employed, or not in work) or not vulnerable, by ethnic group.

Here we see that for all groups, those in a vulnerable economic status are less likely to have a partner in relatively secure work compared with those in a more secure economic position. But there is also substantial variation within groups.

For both those in more secure employment themselves and those economically vulnerable, white British, other white and Indian ethnic groups are more likely than the other groups to have a partner in relatively secure employment. This also arises in a context in which Bangladeshi, black African and black Caribbean groups are less likely to be able to rely on savings to tide them through short periods of income loss.

Figure 3: Partnership economic status among those of working age in more or less secure employment situation, by ethnic group

Source: Labour Force Survey, first quarter of 2016 to fourth quarter of 2019

To what extent are these outcomes ‘new inequalities’?

The differential effects of the crisis across ethnic groups derive from existing inequalities, which mean that that some ethnic groups were already more likely to be working in more marginal or lower paid or part-time work, relatively highly segregated occupationally, and more vulnerable to the loss of an earner in the household, as a result of fewer households with more than one earner.

To that extent, the crisis is not creating ‘new inequalities’, but it is heightening existing ones and revealing the vulnerability of specific groups and occupational niches to economic shocks.

Nevertheless, while this vulnerability was already in evidence prior to the crisis the widening of ethnic inequalities and the reduction in the alternatives offered by self-employments for those with difficulty accessing employment opportunities may entrench inequalities for future generations. This is happening at a time when they had appeared to be declining to some extent.

At the same time, some ethnic groups, such as those of Indian ethnicity, are relatively advantaged, in both earnings and savings. This is in part due to occupational clustering. For example, 4% of Indian men and 3% of Indian women are medical doctors, making up 13% of doctors overall. Occupational clustering does not therefore necessarily imply disadvantage or marginalisation: it depends on the nature of the occupational concentration. But as has been illustrated in the discussions about mortality among hospital staff dealing with Covid-19, these forms of occupational clustering also bring their own risks.

The crisis thus brings into sharp relief the consequences of economic clustering and niche economies. It raises questions about how they arise: the extent to which they stem from positive choices and aspirations, or from different opportunities and forms of exclusion.

Even if some occupational concentration may stem from active evaluation of trade-offs in times of relatively prosperity, events such the Covid-19 crisis can dramatically alter the relative costs and benefits. Greater attention to how such occupational clustering arises may have payoffs for reducing inequality both at times of crisis and in the longer term.

What else do we need to know?

Inferences about the current economic effects of the crisis across ethnic groups, such as those set out here, are derived from studying different groups’ economic and occupational position prior to the lockdown. While it is likely that recent economic status will translate in the ways expected into current economic status, variation within industries and across geographies in the severity of the shock means that it remains important to identify more precisely who was affected when we have further information on actual effects.

Future work will therefore use data currently being collected or soon to be available to assess directly the effects of the lockdown on different ethnic groups’ economic activity and household income, as well as consequences of disruption to labour market entry for graduates.

Some effects will be somewhat longer in becoming apparent, including those stemming from disruptions to schooling. Nevertheless, in the shorter term, it will be possible to examine the extent to which children from different ethnic groups have had different educational inputs during the school closure period, and evaluate the potential consequences.

Related question: What will be the impact of lockdown on children's development?

To date, minority ethnic groups have been attaining increasingly highly in education, and their attainment has been less sensitive to family poverty than it is for the white UK majority. Whether that attainment can be maintained in the face of a sustained break in schooling alongside cancellation of exams and disruption in higher education remains an important question for the future.

It should be noted that the ethnic group categories used here are derived from the standard categories asked in census and surveys by the Office for National Statistics. The discussion focuses on the seven larger ethnic groups, for which separate analysis is possible.

All the statistics presented in the figures are from analysis by Lucinda Platt of the Labour Force Survey, pooling all quarters from the first quarter of 2016 to the fourth quarter of 2019 to enable sufficient numbers of minority groups for reliable estimates. It thus represents the average situation for the population across the three years preceding the crisis.

What more can I read?

Are some ethnic groups are more vulnerable to Covid-19 than others? Lucinda Platt and Ross Warwick report on the unequal health and economic impacts of the pandemic on the UK’s minority ethnic groups.

Racism is the root cause of ethnic inequities in Covid-19: Laia Bécares and James Nazroo writing for Discover Society.

Who are UK experts on this question?

- Lucinda Platt, LSE

- Alita Nandi, University of Essex

- James Nazroo, University of Manchester

- Ross Warwick, IFS