From the outset of the pandemic, there were reports of retailers charging exceptionally high prices for certain products, notably hand sanitiser. Investigations by the Competition and Markets Authority have played an important role in quelling the practice.

At an early stage in the pandemic, the UK Competition and Markets Authority (CMA) set up a taskforce to monitor and respond to competition and consumer problems arising from Covid-19. From mid-March to mid-November 2020, the CMA received more than 115,000 complaints from consumers, over 15,000 of which concerned price rises.

One product that stood out was hand sanitiser – not just because of the volume of complaints, but also the scale of the price increase (a median rise of 400%), the growth in demand for the product and its importance in reducing transmission of the virus. These factors led the CMA to open investigations into suspected excessive pricing of this product by retailers in June 2020.

Were the complaints justified or were the price hikes a response to market trends?

The CMA received over 1,800 complaints related to high prices of hand sanitiser between March and June this year. The great majority of these concerned independent retailers: of the 563 complaints that contained precise price and pack size information for analysis, 160 related to independent chemists and 219 related to convenience stores (including symbol group shops).

The complaints were dispersed widely across the UK, with the large majority of retailers receiving a single complaint. As a matter of priority, the CMA focused on cases where precise information on price and pack size was provided, as well as retailers about which there were multiple complaints.

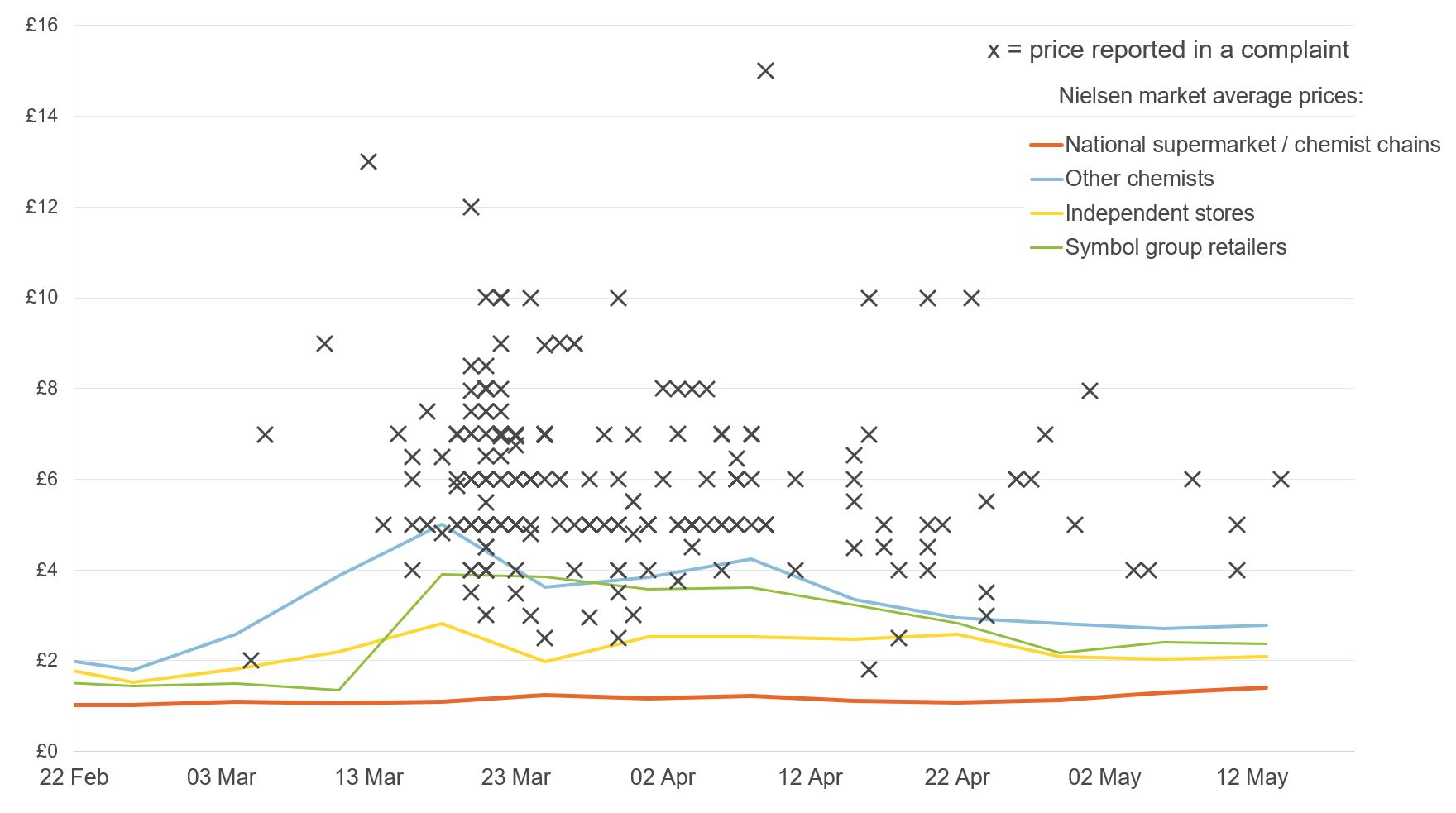

Figure 1 compares prices about which a complaint was made with market average price trends using the top-selling pack size (50ml) of hand sanitiser. Each cross in the chart represents a complaint, showing the price level reported and the date of the complaint. The lines show average price (weighted by volume across all brands) in different retail channels, including supermarkets and chemist chains, other chemists, symbol group retailers and other independent retailers.

Figure 1: Prices reported in complaints and market average prices by retail channel, hand sanitiser (50ml bottles)

Notes: Chemist chains refers to Boots and Superdrug in Nielsen’s categorisation. Three complaints with very high prices (over £19) are not shown in the figure. Crosses may overlap each other.

Sources: CMA (complaints data); Nielsen (market average prices)

Figure 1 shows that prices reported in most complaints were substantially higher than market average prices:

- Prices at large national grocery and chemist chains (the orange line) remained broadly stable at around £1.

- Prices at other retailers, especially independent chemists (the blue line), saw some significant increases: from around £1.50 at the end of February, before the outbreak and government advice on hand washing, to a peak of around £5 in the third week of March 2020, shortly before lockdown.

- Even when compared with the higher market averages in non-supermarket shops, the prices reported in most of the complaints were much higher.

Could changes in the supply chain explain the price increases?

As part of its investigation, the CMA carried out a review of the hand sanitiser supply chain in May 2020. It gathered information from the following industry participants: major UK upstream suppliers of hand sanitiser; national chemist chains; brand-owners of symbol groups (given that a significant number of complaints were reported against symbol shops); and retailers including independent chemists or convenience stores, which also received repeated complaints.

On the basis of the information gathered, it is possible to assess whether the high retail prices of hand sanitiser were a result of higher raw material costs, or whether these augmented prices were necessary to attract the entry of new businesses. Intervention would be justified where neither were the case.

Were hand sanitiser price increases explained by raw material cost increases?

Some media reports ascribed the price hikes to shortages of – and hence cost increases in – ethanol, which is a key ingredient in hand sanitiser. Had this been the case, the price of all hand sanitisers (across all types of retail establishment) would have increased. As Figure 1 shows, this was not the case.

In addition, the main upstream suppliers informed the CMA that ethanol cost increases would only account for a relatively small price increase (and would not justify a doubling or tripling of retail prices), because the cost of other components such as filling fees, thickeners, fragrances, caps and bottles remained broadly unchanged.

Were high prices necessary to attract new business?

As it became clear that hand washing was essential to limiting the spread of the virus, demand for hand sanitiser grew substantially, as did the incentive to supply it. The CMA was told by all large upstream suppliers that they had expanded local production and increased imports of hand sanitiser to meet this increased demand, although they expected that production capacity would take a while to catch up.

Similarly, national chemist chains (which kept prices broadly unchanged) told the CMA that they had actively looked for new suppliers to expand their retail stock. These businesses appear to have taken steps to expand without requiring higher retail prices to do so.

New suppliers such as breweries and distilleries in the UK also responded to supply shortages by shifting production of ethanol for use in hand sanitiser. Rather than attempting to sell these at high retail prices, some simply gave them away to frontline workers. While the quantities are probably small and not available for general consumer use, this example shows that entry to the market can be driven by a myriad of factors during a pandemic, not just higher retail mark-ups.

It is true that some entrants may have been motivated by the prospect of selling at high prices. The large suppliers and chemist chains told the CMA that the pandemic has given rise to short-term opportunities for smaller wholesalers and importers to supply new products. Similarly, analysis of the Nielsen data shows that 16% of revenue relates to brands that were not supplied in the UK pre-Covid-19, and these brands tend to be more expensive than their existing counterparts.

While some new entry to this market may have been driven by high retail prices, it seems that expected and sustained growth in demand for certain products, such as hand sanitiser, is likely to be a much more significant factor that induces a supply response, at least for large upstream suppliers. In any event, higher downstream retail mark-ups are unlikely to benefit upstream suppliers and to be the reason for their expansion.

What action was taken to prevent excessive price increases?

The CMA requested data from retailers that received the most repeated complaints to evaluate their prices and mark-ups. These were then compared with a reasonable range of retail mark-ups estimated based on information from producers on their pricing to different channels and their recommended retail prices (RRPs), pricing by major wholesalers, and from the retailers including responses to the CMA.

The CMA also made ‘mystery shopping’ calls in mid-May to these retailers to verify the prices reported in the complaints, so as to make a priority of retailers that continued to charge high prices.

Of the retailers considered, the CMA found that:

- A small number of pharmacies charged high prices that were not justified by costs, with some extremely high mark-ups. These retailers voluntarily agreed to reduce prices to levels based on either pre-Covid-19 mark-ups, normal mark-ups of other products, and/or the RRPs set by the wholesalers.

- The mystery shopping exercise confirmed that a number of retailers had already reduced their prices since the complaint was reported. In addition, one retailer reduced its price the day after it received the CMA’s information request and another reduced its prices later, around mid-May.

- The prices for the remaining retailers were high relative to market benchmarks but were due to high wholesale costs. Their retail mark-ups appear to be within a reasonable range typical for the product. These retailers usually sell smaller brand products; several of them only supplied on a one-off basis after the outbreak.

In the light of these findings, the CMA closed its investigations on hand sanitiser products in September 2020. It determined that the prices the retailers were charging did not, nor were likely to, infringe competition law.

Outside the retailers with repeated complaints, there were also a significant number of single complaints concerning individual pharmacies. Rather than investigate each one, the CMA engaged with the General Pharmaceutical Council, the regulator of pharmacies, to send a joint letter to over 4,000 pharmacy owners and superintendent pharmacists across Great Britain. The letter provided guidance for pharmacies and encouraged them to set prices for essential products (including hand sanitiser, face masks and paracetamol) that did not include higher than usual mark-ups.

The CMA also carried out advocacy work through symbol groups. Their public announcements and pricing investigations appear to have directly influenced behaviour here. For example, two symbol groups communicated with their retailers, making direct mention of the CMA’s role in enforcing against unreasonable behaviour and highlighting the need to protect their brand image in local communities and refrain from profiteering behaviour.

What can we conclude from the CMA investigations?

Overall, the CMA’s experience in addressing the complaints of price hikes indicates an important role for competition authorities as observers of markets – to assess firm conduct and maintain public trust by preventing the most severe abuses while taking care not to disrupt supply responses. This contrasts with the alternatives of direct price regulation or doing nothing, even while there were questions about the basis for applying competition tools to tackle short-term price hikes.

The experience also highlights the importance of competition authorities understanding how markets work in practice, and responding flexibly and at speed. The CMA is currently required to open an excessive pricing investigation against a firm to be able formally to acquire relevant information from it. There is a need for the tools at their disposal to be updated to reflect the volume of real-time data being generated and the need to be able to act relatively quickly, especially in emergency situations such as the Covid-19 pandemic.

Where can I find out more?

- Hand sanitiser products: suspected excessive and unfair pricing: June 2020 case page of the Competition and Markets Authority.

- Update on the work of the CMA’s Taskforce: July 2020 page on CMA work to identify, monitor and respond to competition and consumer problems arising from coronavirus and the measures taken to contain it.

- Tackling the COVID-19 challenge – a perspective from the CMA: Article by Will Hayter at the CMA in the Journal of Antitrust Enforcement.

- How should competition policy react to coronavirus? Institute for Public Policy Report paper by former CMA chair Andrew Tyrie.

Who are experts on this question?

- The Centre for Competition Policy (CCP) at the University of East Anglia has academic experts in all areas of competition and consumer policy. CCP contributors to this article include: Paul Dobson, Sean Ennis, Amelia Fletcher and Bruce Lyons.