The post Should central banks develop their own digital currencies? appeared first on Economics Observatory.

]]>With over a quarter of all payments in the UK made via contactless methods, consumers are looking for convenient ways to spend their money in a digital world. The banking sector as a whole is starting to increase its digitalisation with the emergence of digital banks such as Monzo, Revolut and Starling in the UK, and the growth of vendors such as Alibaba’s Ant Financial and Tencent’s WeBank in China’s financial sector.

One of the biggest changes coming to the banking sector will be the emergence of central bank digital currencies (CBDCs), which are digital currencies created and controlled by central banks such as the Bank of England in the UK, the European Central Bank (ECB) in the Eurozone and the Federal Reserve (the Fed) in the United States.

Comparisons are often made with cryptocurrencies since some proposed CBDCs could make use of the ‘blockchain’ technology that is used in many popular cryptocurrencies. But CBDCs will be controlled by central banks via their own private blockchains to ensure privacy and avoid the many security and volatility issues faced by cryptocurrencies. As a result, CBDCs will be quite distinct from cryptocurrencies such as Bitcoin and Ethereum.

In this article, we explore what CBDCs are, why governments are trying to create them, how far advanced they are, and the risks associated with these new currencies.

What are CBDCs?

CBDCs are forms of regulated, government-issued electronic money. While most cryptocurrencies, like Bitcoin, are decentralised assets and a pure ‘peer-to-peer’ version of electronic money (Quinn, 2021), CBDCs will be governed by central banks such as the Bank of England, the ECB and the Fed.

CBDCs are being developed to replace national currencies and move to a cashless society. Indeed, 86% of central banks are actively researching CBDCs, 60% are experimenting with CBDCs, while 14% are deploying pilot projects, according to a recent Bank for International Settlements (BIS) survey.

The Bahamas became the first nation to introduce CBDCs with the ‘sand dollar’ in October 2020, while Nigeria became the first African country to launch a digital currency – the eNaria – in October 2021. In China, the digital renminbi (e-CNY) is being developed for cross-border use, while in the United States, two CBDC initiatives are under way. In September 2021, Fed chair Jerome Powell said that the central bank is ‘working proactively to evaluate whether to issue a CBDC… I think it’s more important to do this right than to do it fast’.

Why are governments trying to create CBDCs?

There are several reasons why governments might introduce CBDCs. Here, we discuss some of the most important motivations.

First, there is a threat posed by cryptocurrencies and ‘stablecoins’ like Tether. Almost every central bank has written white papers on cryptocurrencies. While many cryptocurrencies could never replace a national currency due to practical reasons – such as the large transaction fees, scalability issues in terms of transactions and the large volatility (see Quinn, 2021 for an excellent discussion) – central banks are concerned that they are being left behind in this digital revolution and want to move with the times. The growing interest and use of cryptocurrencies are a challenge to national currencies and issuing CBDCs will help counteract that growth.

Second, CBDCs should improve the efficiency and safety of both retail and large value payment systems. On the retail side, the focus is on how a digital currency can improve the efficiency of making payments, for example, by speeding up transactions at the point of sale, online and peer-to-peer. There could also be benefits of having a CBDC for wholesale and interbank payments since, for example, it could facilitate faster settlement and extended settlement hours. Further, CBDCs could improve cross-border payment efficiency. They have the potential to improve counterparty credit risk for cross-border interbank payments and settlements by offering 24-hour availability, anonymity and eliminating counterparty credit risk for participants.

Third, the introduction of CBDCs would speed up the transition to a cashless society. Cash use is falling at a dramatic rate due to the ease of payments using cards, apps and contactless payments. Cash costs money to mint – for example, a $100 note costs 14 cents to print – so a cashless society reduce costs for central banks. Cash is also difficult to trace, which makes it attractive for tax evasion, money laundering and illegal transactions. It poses a greater security risk when transporting funds and making payments as there is no record of exchange. It could be that future governments wish to remove cash to reduce crime and improve tax receipts.

Fourth, CBDCs may improve financial inclusion. More than 1.7 billion adults around the globe (and 4% of the UK population) are ‘unbanked’, referring to a person ‘not having access to the services of a bank or similar financial organisation’. CBDCs could promote financial inclusion among these unbanked populations by giving them access to a safe place for their savings and eventually, access to credit.

What are the risks of CBDCs?

One concern about CBDCs is that they would require centralisation of the banking sector, which would amplify the threat of cyber-attacks. Just as the failure of any one bank erodes confidence in banking, a CBDC could potentially relocate this risk to central banks. This would negate the benefits of strategic risk-sharing structures and distance between participants in the financial system.

That said, the technology of the blockchain is very secure and transactions are highly compartmentalised, which means that the central bank could potentially operate a distributed system, thereby spreading the risk and consequences of any possible cyber-security breach more widely.

A CBDC could also represent a potential encroachment on consumer privacy and protections. With a CBDC, the central bank could easily block the use of funds of individuals or groups who fall out of favour with the government. The use of money (a public good to which equal access is a human right) and how it is saved, sent, spent and secured, should be as free as possible while maximising the penalty on bad actors. US Congressman Tom Emmer wrote: ‘Central banks increase control over money issuance and gain insight into how people spend their money but deprive users of their privacy,’ adding, ‘CBDCs would only be beneficial if they are open, permissionless and private.’

There is a concern that financial inclusion has declined further during the pandemic, as efforts to digitise money have been supercharged. This could be exacerbated with the introduction of CBDCs as they may be beyond the reach of those with older devices or without access to digital wallets. Care will be needed to avoid further disenfranchising the old, poor and vulnerable.

The future

It is inevitable that central banks will issue CBDCs in the future given the dramatic move to online banking and the speed of digitalisation. The design of these CBDCs may differ substantially across nations, but in all cases, the central bank will still be in charge of the currency.

They will no doubt disrupt the banking industry and enable more people to be banked, offer faster services and deliver credit to businesses on better terms, while also preserving liquidity and efficiency in capital markets. While some degrees of privacy will be lost, the benefits from protection against fraud and other crimes may more than compensate.

Where can I find out more?

- The Bank of England’s CBDC website offers lots of resources on CBDC design and implementation.

- The ECB’s CBDC website offers details on the research of CBDCs at the Eurozone’s central bank.

- The BIS executive summary on CBDCs as well as links to other policy documents.

- The CBDC tracker offers up to date information on CBDCs status around the globe.

- CBDC considerations, projects and outlook.

Who are the experts on this question?

- Tom Mutton, Director Fintech, Bank of England

- Manisha Patel, Senior Analyst, Digital Currencies Team, Bank of England

- Raphael Auer, Principle Economist, Bank of International Settlements

- Linda Schilling, Olin School of Business at Washington University, St Louis

- Eswar Prasad, Cornell University

Author: Andrew Urquhart, University of Reading

Photo from Wikimedia Commons

The post Should central banks develop their own digital currencies? appeared first on Economics Observatory.

]]>The post How are crime trends in England and Wales changing during the pandemic? appeared first on Economics Observatory.

]]>The lockdown and post-lockdown periods show very different composition of crimes compared with the average seasonal rates. But the effects on crime rates may be lasting: the pandemic has aggravated inequality and this is already palpable in criminal outcomes.

The vaccine rollout may bring back normality in many aspects in the short term. But with more deprived areas showing higher rates of violent crime since the pandemic started, vaccinations may not be able to fix the social damage caused by the crisis.

How has lockdown changed crime rates?

Most developed economies realised the gravity and spread of coronavirus between February and March 2020. In response, governments forced their populations into lockdown and imposed significant restrictions on mobility.

Data from Police UK show that in England and Wales, crime decreased in most categories during the first lockdown, with only anti-social behaviour and drug offences at higher rates than expected. Offences motivated by material gain – known as ‘acquisitive crimes’ – were much lower than they had been in similar months in previous years. Burglaries and robberies are much less likely to take place with shops shut and more people staying at home.

Figure 1: Anti-social behaviour offences in England and Wales

Source: Authors’ analysis of data from Police UK.

Anti-social behaviour was much higher during lockdown than in previous years, by about 25% - see Figure 1. Since such behaviour includes severe breaches of social distancing measures, this means that lockdown created a new type of offence for the police to target.

Drug offences were 17% above average as users continued to require a supply of drugs (see surveys by Release in the UK and GDS globally). The increase is unlikely to be driven by higher drug activity, but rather the result of more arrests as identifying dealers is easier with reduced mobility of citizens (Langton, 2020).

Within crime categories, the police also documented a change in the type of offences. While violent offences were lower on aggregate terms during lockdown, they were much more likely to be domestic incidents. Crimes committed by partners increased substantially, while it was much less likely for victims to suffer abuse from a former partner or unknown aggressor (Ivandic et al, 2020). Intuitively, as lockdown changes social interactions to be restricted at home, it affects all other aspects of human life, including criminal offences – see Figure 2.

Figure 2: Weekly calls for domestic incidents/crimes in London in 2019 and 2020

Source: Data from the London Metropolitan Police Service analysed in CEP research.

What happened to crime after the first lockdown?

Once the first lockdown was lifted in June 2020, crime remained at significantly lower levels on average. This is likely to be because many social restrictions remained in place or were encouraged. For those crimes that did take place, the composition of offence types was very different from that observed in previous years – see Figure 3.

Figure 3: Composition of crimes for the period from June to September in 2019 and 2020

Source: Authors’ analysis of data from Police UK.

Across the country, only anti-social behaviour and drug offences show higher levels. But this is not the case universally. In fact, crimes have become more concentrated in deprived areas. Spatially, the economic impact of the pandemic is starkly clustered.

For example, this interactive map shows increases in the number of claimants of Jobseeker’s Allowance and Universal Credit by local authority between March and September 2020. The map shows some areas not suffering much (probably as many people were able to retain their jobs by working from home), with others seeing the number of people seeking unemployment benefits more than doubling during those months.

By dividing the country into areas based on high and low claims for Jobseeker’s Allowance and Universal Credit, it can be shown that high-claimant areas have seen an increase in crimes since lockdown was lifted (Kirchmaier and Villa-Llera, 2020).

These high-claimant areas are more likely to have higher proportions of Black and Asian population, a higher proportion of lone parent families and worse health outcomes. They have experienced a greater rise in crime compared with previous years, conditional on area-specific and seasonal trends. This is driven by higher rates of violence and public order offences, revealing high social unrest.

By analysing regional variation as well as the impacts of Covid-19 on labour markets, it is possible to identify high-risk groups within the population. These groups include areas with a higher proportion of welfare claimants prior to the pandemic and an above average increase in claims since March 2020.

About 12% of local areas are in this high priority category. Many of them have experienced higher levels of offences in many acquisitive crime categories (such as burglary, shoplifting, bicycle theft and vehicle offences). In this case, deprivation – together with above average damage to economic opportunities – does appear to result in higher acquisitive crimes, as traditional analysis of the economics of crime predicts (Becker, 1968; Elrich, 1973).

Covid-19 has highlighted several important inequalities within UK society. These inequalities persist even in a country where government measures can support people in unemployment and furlough with generous support schemes, and where health is public and universal. Despite all these efforts, the inequality is clear. Further, different economic groups are clustered spatially, concentrating many of the costs of the pandemic.

Different neighbourhoods have been affected differently by the pandemic. Deprived neighbourhoods are experiencing more crimes in certain categories, relative to normal patterns.

Different offence types call for a renewed allocation of policing resources. But changes in policing resources alone will not solve the problem of rising inequality. Social policy must be coordinated and aim for job creation, particularly for those sectors and areas most in need.

Where can I find out more?

- Covid and changing crime trends in England and Wales: Report by the Centre for Economic Performance, which analyses crime trends during the first lockdown and post-lockdown period and the correlation with economic performance. It highlights the important spatial differences in economic performance and the concentration of crimes.

- Six months in: pandemic crime trends in England and Wales: Study of crime trends and how crime was expected to evolve during the first lockdown and post-lockdown period, highlighting how permanent changes in mobility may have a lasting impact in the composition of crime.

- Crime in the era of COVID-19: Evidence from England: Study of crime trends in England, including the second lockdown (October 2020), which concludes that the lockdown effect does not differ strongly between different lockdown periods.

Who are experts on this question?

Crime during the pandemic:

Job destruction during the pandemic:

Authors: Tom Kirchmaier and Carmen Villa-Llera

Image by natefarr from Pixabay.

The post How are crime trends in England and Wales changing during the pandemic? appeared first on Economics Observatory.

]]>The post Perspective matters appeared first on Economics Observatory.

]]>To solve any difficult problem, there is value in looking at things from a range of perspectives. Using different measures and methodologies can help us to draw nuanced conclusions, and a balanced approach is critical for designing good policy.

With Covid-19, it’s no different. Arguably, this is all the more important because the challenges posed by the pandemic have called for such extreme measures. Protecting the population has meant nation-wide lockdowns. The Coronavirus Job Retention Scheme has kept millions of furloughed workers from losing their jobs. And medical innovation has been supercharged in pursuit of new vaccine technology.

It is certainly striking that the global economy has been hurt by a collection of viral particles that could fit into a single Coca-Cola can – a fact highlighted by Tim Harford in a recent episode of BBC Radio 4’s More or Less.

Here at the Economics Observatory, our commitment is to provide balanced, evidence-driven analysis of the challenges facing the UK economy – from Covid-19 and Brexit to climate change and inequality. Grappling with these questions has revealed the value of analysing questions from more than one angle. Sometimes taking a step back and getting a ‘zoomed-out’ view can help researchers spot particular patterns. In other cases, it’s useful to drill down into the data, uncovering the hidden truths behind the headlines. This week’s articles have done both.

Measuring the crisis

Meeting the challenges of Covid-19 has required mammoth levels of public spending, leading governments around the world to borrow vast sums of cash. This week we asked whether the balance sheets of central banks – often the ‘lenders of last resort’ – can handle the challenges of Covid-19.

To address this question, Willem Buiter takes what I call a zoomed-out approach, focusing on the bigger picture of central banks’ assets and liabilities in economies around the world.

What we learn is that in response to the crisis, the European Central Bank, the US Federal Reserve and the Bank of Japan have all dramatically increased the size of their balance sheets, representing a surge in central bank lending (see figure below). Viewing the crisis from this perspective helps us see the shift in its historical context, highlighting how Covid-19 differs from, say, the global financial crisis of 2007-09.

Balance sheet (% of 2019 GDP)

Source: Bloomberg Finance LP, Deutsche Bank

Yet ‘zoomed-in’ analyses are also vital for measuring the impacts of the pandemic. This week, the Office for National Statistics released the latest labour market overview, and Stuart McIntyre – of the Fraser of Allander Institute (Strathclyde) – drilled into the data in search of the story behind the headlines.

While several reports highlighted the overall unemployment rate of 5.1%, Stuart’s Observatory article provides a sector-by-sector, region-by-region and age-by-age analysis of the data. As he points out, headline measures such as the unemployment rate ‘do not reflect the full scale of the economic crisis’. Looking at the charts below, it is clear that effects of the pandemic on jobs are uneven and vary greatly according to a number of factors.

Payroll employment by age

Source: Office for National Statistics

Changes in payroll employment January 2020 to January 2021 by sector

Source: Office for National Statistics

By taking a close-up look at the data, we can see that people working in accommodation and food services, or in the arts and recreation, have a very different story to tell compared with those employed in public administration. And it is clear that young people continue to bear the brunt of Covid-19 job losses.

Just as Willem’s work gave a useful view of the rapid change in public borrowing and spending, Stuart’s zoomed-in analysis of the labour market data helps reveal the diverse experiences contained within headline stats.

Brexit means more than just Brexit

Like Covid-19, Brexit is a challenge that is affecting the county in a number of different ways. The final trade agreement requires a complete rewrite of the UK’s commercial relationship with the European Union (EU) – a task grand in scale and daunting in scope. But within this, all manner of industries and individuals are affected, and issues like the future of Scotland's fishing industry, music and theatre tours, and even lorry drivers’ lunches have quickly drawn widespread attention.

In response to these varied and often contradictory concerns related to the UK’s exit from the EU, Observatory contributors have once again risen to the challenge of offering a range of perspectives.

This week Christopher Coyle – of Queen’s University Belfast – explores the impact of Brexit and other large events on the value the pound. He shows how, since the referendum, the strength of the pound has fallen significantly (see figure below). He argues that this ‘seems to reflect a generally negative outlook’ of the UK’s economic prospects outside the EU.

Pound/Euro daily exchange rate 2015-2021

Source: Bloomberg

Looking at currency fluctuations is an example of taking a zoomed-out view of the economy. We can trace the effects of significant events like Brexit or the pandemic through aggregate dynamics, such as investors buying or selling currency en masse. These movements help tell an underlying story, in this case, the lack of faith in UK businesses in the near future.

But, once again, other stories can be uncovered by taking a more zoomed-in look at the situation. This week, Joel Carr, Joanna Clifton-Sprigg, Jonathan James and Sun?ica Vuji? investigate the impact of the Brexit vote on hate crime in the UK. By analysing crime statistics from the months leading up to and immediately following the referendum, they find that Brexit was followed by a 15-25% increase in race and religious hate crime in England and Wales.

While this does not necessarily imply that Brexit directly caused rises in such crimes, the authors argue that a series of economic and political factors may have resulted in boththe Brexit vote and the changes in hate crime incidents.

Brexit is a complex and multidimensional issue. Analysing its true effects requires a balanced approach that examines broad measures, including currency value or GDP alongside individual experiences, such as business closures, crime or changes in household earnings.

The limitations of measurement

For all the value of zooming in and out in our analysis, there are, in my view, still some limitations to measurement.

This week, another grim milestone was reached. The United States surpassed half a million Covid-19 deaths, with the UK reportedly reaching over 135,000 lives lost. From whatever angle you look at numbers like this, the immense suffering brought about by the pandemic is clear.

But rather than dismissing the role of balanced and impartial analysis, this should be seen as a rallying call for continued rigour in the struggle against Covid-19.

Yet there are now some reasons to be hopeful. This week the UK reported that over 18 million (first) vaccine doses had been administered, with the prime minister announcing on Monday the ‘roadmap’ out of lockdown –a plan driven by data, not dates.

Central to this data-focused strategy is a set of measures that involve looking at the pandemic at both a national level, as well as up close. Vaccinating the population, moving out of lockdown and then ‘building back better’ will all require intelligent policy informed by several different perspectives and methodologies. If we have learned anything over the last year, it should be that perspective matters.

Author: Charlie Meyrick, Economics Observatory Manager

Photo by Nadine Shaabana on Unsplash

The post Perspective matters appeared first on Economics Observatory.

]]>The post Did the vote for Brexit lead to a rise in hate crime? appeared first on Economics Observatory.

]]>Hate crime is defined as ‘any criminal offence which is perceived, by the victim or any other person, to be motivated by hostility or prejudice towards someone based on a personal characteristic’ (Home Office, 2017). It is categorised by race or ethnicity, religion or beliefs, sexual orientation, disability and transgender identity.

The rise in race and religious hate crime mostly took place in the first three months after the referendum and was relatively larger in areas that voted for Brexit. While the increase coincided with the referendum, it could have been correlated with the vote itself, rather than having been triggered by it. Specifically, it is possible that other economic and political factors resulted in both the Brexit vote and the changes in hate crime incidents.

The vote may also have led to increased reporting of hate crimes by victims and witnesses, or better recording by the police. Both trends could have been further amplified by traditional and social media. Recent research uses various data sources on hate crimes – such as data collected from the UK police forces by Freedom of Information (FOI) requests and/or data collected by the Community Safety Partnership (CSP) areas – and various analytical methods to eliminate these other potential channels.

The research suggests that the Brexit referendum triggered an increase in hate crime immediately after the vote (Carr et al, 2020). Similar recent studies highlight the rise in hate crime after the referendum, but focus less on the underlying mechanisms (Schilter, 2020; Devine, 2018).

Although the estimated effects seem considerable, a 15-25% rise in recorded hate crime translates into approximately 2,000 additional hate crimes in the third quarter of 2016 in England and Wales (Carr et al, 2020). But this finding is likely to understate the effects of the referendum, as typically only half of hate crimes are ever reported (Home Office, 2020). To put this number in perspective, international hate crimes on a monthly level in 2016 hovered around 300 in Germany (xenophobic hate crimes) and over 400 in the United States.

Did areas that voted heavily for Brexit experience a larger rise in hate crimes?

According to one study, the increase in hate crime differed between the pro-Leave and pro-Remain areas (Albornoz et al, 2020). Their evidence suggests that hate crimes rose more in areas that voted to remain in the EU. The logic for this is that since behaviour is dictated by individuals’ preferences – as well as by a desire to conform to social norms – areas that voted to remain experienced a greater ‘surprise’ by the referendum result, and this may have led to an increase in hate crime.

In contrast, it can also be shown that hate crimes rose more in areas that voted to leave the EU (Carr et al, 2020). Figure 1 shows the actual and ‘synthetic’ racial and religious hate crimes (RRHC) in pro-Leave (Panel A) and pro-Remain (Panel B) areas. Data from other crime categories are used to construct a weighted combination (‘synthetic control crimes’) of these crimes to estimate what would have happened in the absence of the referendum (a ‘counterfactual’ scenario). The control is constructed in order to make the true RRHC and the synthetic RRHC as similar as possible prior to 2016.

The pre-referendum trends of the actual and synthetic RRHC follow each other closely in the three years running up to the referendum, with no significant deviations occurring in either panel before the vote (see Figure 1). After the referendum, in July 2016, there is a significant visual jump in the trend of the actual RRHC (pink line) relative to the synthetic RRHC (navy line).

This jump is more pronounced in pro-Leave areas. One possible explanation is that there were more people in pro-Leave areas who sympathised with, and then acted on, the anti-immigration sentiment revealed by the referendum. But it should be emphasised that it is not necessarily the pro-Leave voters who committed hate crimes following the vote.

Figure 1: The impact of the Brexit referendum on hate crime in pro-leave and pro-Remain areas

Panel A: Pro-Leave areas

Panel B: Pro-Remain areas

Note: RRHC - racial and religious hate crimes; Actual RRHC - actual data; Synthetic RRHC - comparison group. Source: CSP

Which groups have been most affected by changing patterns of hate crime?

Evidence shows that the increase in hate crime varied depending on the proportion of young men in the local area (Carr et al, 2020). This suggests that young men could be more susceptible to public information shocks than other population groups.

Hate crimes cause social unrest, whereby certain ethnic groups do not feel welcome, hence they feel unsafe in a particular community. There is also some evidence to suggest that hate crimes increased more in areas with a low percentage of minority and migration populations (Carr et al, 2020). The larger shocks in low minority areas grant support to ‘contact theory’, which argues that if individuals have more (positive) contact with minorities, they are less likely to view these groups as a threat or an ‘unknown entity’ (Allport, 1954; Rozo and Urbina, 2020).

It is important to note that it is difficult to connect the political disposition of an area with the level of hate crimes, as minorities may choose to not to live in such areas. This is clear from a study of the 2009 Swiss referendum vote on the construction of new minarets and its impact on the location choices of migrants in a traditional destination country (Slotwinski and Stutzer, 2015).

The researchers report: ‘The symbolic restriction of prohibiting the construction of new minarets was heavily discussed and interpreted as a signal of limited openness towards foreigners.’ The result of the referendum, which like the Brexit vote was contrary to the prediction of the polls (Brexit poll tracker; Swiss vote to ban construction of minarets on mosques), resulted in large drops in the probability that foreigners moved to municipalities that voted against the construction of new minarets. Research by Daniel Müller for Austria has similar results: foreigners sort into communities with more positive attitudes towards migrants.

Contact theory suggests that with sufficient positive contact, individuals are less likely to either commit a hate crime at any point, or be induced to commit a crime after a shock event. As such, one would expect to find both higher levels and shocks of hate crimes in low minority areas.

Could other factors explain the post-referendum increase in hate crime?

There is strong evidence that racial or cultural prejudice is an important component of attitudes towards immigration (Hall, 2014; Dustmann and Preston, 2007) and that this is restricted to immigration from countries with ethnically different populations (Dustmann and Preston, 2007).

There is also suggestive evidence that media – both traditional and social – played a role in increasing hate crime after the Brexit referendum. But these effects are rather small (Carr et al, 2020). Nonetheless, both traditional and social media can instigate acts of bias through perpetuating or legitimising stereotypes and, as a result, contribute to increases in hate crime (Hall, 2014). Recent research shows that social media can lead to a rise in hate crime (Müller and Schwarz, 2019; Bursztyn et al, 2020; Ivandi? et al, 2019).

What do we know about the effects of other shock events on hate crime?

Various studies consider the effect of terrorist attacks – such as 9/11 in the United States and the London 7/7 bombings – on subsequent hate crimes against Muslims, Arabs and others perceived to be Middle Eastern (Swahn et al, 2003; Deloughery et al, 2012; Hanes and Machin, 2014). For example, one study looks at the effect of international jihadi terrorist attacks on local anti-Muslim hate crimes in the Greater Manchester area (Ivandi? et al, 2019).

In these cases – which are most often related to crimes of anti-religious or anti-immigrant nature – the subsequent hate crimes are categorised as ‘retaliation’. The perpetrator is motivated by a desire to retaliate against an attack that they perceive as being aimed at ‘their group’ or ‘their community’.

As in the case of terrorist attacks, unexpected results of contentious elections or referendums have the potential to influence people’s views and their perception of social norms. Research on hate crime has increasingly focused on the effects of elections, especially those with an undertone of xenophobia or anti-immigrant sentiment.

For example, some studies of political events consider changes in hate crime patterns following the election of Donald Trump in 2016 (Sims Edwards and Rushin, 2019; Levin and Grisham, 2016; Jenkins, 2017), while others consider the role of additional factors such as social media in the escalation of hate crimes (Müller and Schwarz, 2019).

Conclusions

Increase in hate crimes after the Brexit referendum suggest that the result created a public information shock, which in turn led to a re-evaluation of society’s tolerance towards racist action and induced some individuals to commit a hate crime. While the temporary nature of the hate crime rise suggests that social norms can change quickly, this change might not be long lasting.

Although social media played a role in fuelling some of the increase in hate crime, there is also evidence of social media campaigns that rallied against the rise (#SafetyPin campaign). Furthermore, just over a month after the referendum, the government announced that prosecutors would be urged to push for tougher sentences for those committing hate crimes (BBC News, 2016). Additional funding for protective security measures at vulnerable faith institutions was also pledged.

This combination of measures raised the cost of committing hate crime and in turn increased the cost of breaking the social norm. It may explain why the effect has not lasted.

Where can I find out more?

- Brexit and hate crime: why was the rise more pronounced in areas that voted Remain? Facundo Albornoz and colleagues suggest that because the referendum was a source of new information about society’s overall preferences over immigration, it enabled those holding anti-immigrant sentiments but living in areas that are generally supportive of diversity to externalise their views.

- Trump and racism: what do the data say? Evidence summarised by the Brookings Institution.

- Do Trump tweets spur hate crimes? Scientific American summarises a 2018 study, which makes a strong case that the then president’s Twitter activity encouraged anti-Muslim crime.

- In Germany, online hate speech has real-world consequences: The Economist summarises a 2018 study, which finds that anti-refugee rhetoric on Facebook is correlated with physical attacks.

- Jihadi attacks, media, and local anti-Muslim hate crime: Ria Ivandic and colleagues at LSE’s Centre for Economic Performance analyse data from Greater Manchester Police, which reveal a spike in Islamophobic hate crime and incidents following ten international jihadi attacks.

Current research projects investigating changing patterns of hate crime

- Demos looks at hate speech on Twitter following the referendum.

- HateLab is a global hub for data and insight into hate speech and crime, including work on the rise in Brexit-related hate crime.

- Stop Hate UK is one of the leading national organisations working to challenge all forms of hate crime and discrimination, based on any aspect of an individual’s identity. Stop Hate UK provides independent, confidential and accessible reporting and support for victims, witnesses and third parties.

Who are experts on this question?

Authors: Joel Carr, Joanna Clifton-Sprigg, Jonathan James, Suncica Vujic

Photo by Askar Karimullin from iStock

The post Did the vote for Brexit lead to a rise in hate crime? appeared first on Economics Observatory.

]]>The post Are Bitcoin and other digital currencies the future of money? appeared first on Economics Observatory.

]]>These ‘blocks’ are generated around once every ten minutes by a user of the network, who receives a reward in the form of newly issued Bitcoin. Which user generates this block, and therefore receives the reward, is determined by ‘proof of work’: using computing power to guess repeatedly a very large random number, with the new Bitcoin awarded to the user who guesses closest to this number. This process is known as ‘mining’ Bitcoin. The size of the reward tends towards zero over time, ensuring an absolute limit of 21 million on the quantity of Bitcoin in existence.

What are the advantages of Bitcoin over existing currencies?

According to its supporters, Bitcoin has two advantages over existing currencies. The first is that its supply is limited, making it impossible for a central authority to issue it in quantities that would devalue it. This means it is much less vulnerable to hyperinflation crises, such as those seen in Weimar Germany, Zimbabwe or Venezuela. But a limited supply can also be a weakness, as it makes it impossible to control deflation – a phenomenon that can also lead to very severe economic consequences (Bordo and Filardo, 2005).

The second claimed advantage of Bitcoin is that all transactions are permanent and immutable. When money is held in a bank account, that bank could theoretically expropriate the money from its user and claim that it never existed. With Bitcoin, this is impossible, because the database on which transactions are recorded cannot be edited by any central authority. Bitcoin is thus often described as ‘trustless’, because it does not require its holder to trust a financial institution not to expropriate it.

These advantages are very much theoretical. Hyperinflation is not currently a major problem in advanced economies, and while financial institutions have been known to engage in fraudulent practices, they are typically more subtle than simply to seize their customers’ funds and deny that they had ever existed.

In practical terms, the main advantage for users of Bitcoin is its anonymity, which allows it to be used to break the law with a lower risk of prosecution. One 2019 study found that 46% of all Bitcoin transactions involved illegal activity, accounting for around $76 billion per year (Foley et al, 2019). The most common forms of illegal activity using Bitcoin are the purchase of illegal drugs and money laundering. It is also frequently used to solicit anonymous payments during blackmail and extortion schemes.

Banks dealing with cryptocurrency platforms have historically struggled to comply with ‘know-your-customer’ regulation and several governments – most recently the French Minister of the Economy and Finance – have sought to crack down on the anonymity afforded by Bitcoin.

What are the disadvantages of Bitcoin compared with existing currencies?

In economic theory, money is said to have three primary functions: a medium of exchange; a store of value; and a unit of account. How well does Bitcoin fulfil these roles?

As discussed, Bitcoin is an excellent medium of exchange for transactions that require anonymity. But using it for other transactions is often prohibitively expensive. The average Bitcoin transaction fee during 2020 has ranged from 28 cents on 2 January to $13.41 on 31 October.

Furthermore, transferring Bitcoin without going through a third party, such as a crypto exchange, can be logistically challenging for those without a background in computer science. Most traders therefore use an exchange or a virtual wallet handled by a third party. But this means that the currency is no longer trustless, and Bitcoin holders have historically lost large sums of money to careless or fraudulent third parties. The most famous such episode was the theft of $460 million worth of Bitcoin held in the Mt. Gox Bitcoin exchange in 2013.

The usefulness of Bitcoin as a store of value is limited by its volatility. In the year to 9 December 2020, the US dollar value of Bitcoin – and therefore the quantity of goods that can be bought with Bitcoin – changed by an average of 2.22% per day. The price of Bitcoin has risen considerably in that time and advocates often argue that the cryptocurrency is a good store of value because its price will continue to rise over time.

The future price is inherently unpredictable, but even if optimists are correct that its price will rise, this is only an argument that Bitcoin is a good speculative investment – not that it is a useful form of money (Baur et al, 2018). Countries typically aim to have a stable currency rather than an appreciating but highly volatile currency, because the former is much more conducive to a healthy economy. This volatility also limits the effectiveness of Bitcoin as a unit of account: denoting the value of an asset in Bitcoin makes little sense when the real value of Bitcoin changes by an average of 2.22% per day.

Figure 1: Closing price of Bitcoin (USD), 2016-2020

Source: coindesk.com

These problems are significant, but may be surmountable in the long term. Perhaps a much more profound barrier to the widespread adoption of Bitcoin is the scalability of the blockchain. Each block is currently equipped to handle 1MB of data, meaning that it can only process between 3.3 and 7 transactions per second (Croman et al, 2016). During a period of intense speculative trading in 2017, the blockchain was overwhelmed by the quantity of requested transactions, causing the average Bitcoin transaction cost to rise to over $55.

This limit is several orders of magnitude too low for Bitcoin to function as a country’s main currency. For comparison, Visa alone handles around 1,736 transactions per second, and the company claims that its network can handle over 24,000 transactions per second. Despite several proposals to alleviate this scalability problem, it is not clear that a solution exists, or that any solution could gain the confidence of enough Bitcoin stakeholders to be implemented successfully.

These problems with Bitcoin resulted in several attempts to create new digital currencies that solve these volatility and scalability problems – some of which have come to be known as ‘stablecoins’.

What are stablecoins?

A stablecoin is a cryptocurrency that has its market value pegged to another asset or basket of assets. If traditional cryptocurrencies could be said to have a floating exchange rate, in that their price is allowed to fluctuate, stablecoins have a fixed exchange rate, in that their price is held constant by the guarantee of a central authority.

The most widely used stablecoin is Tether, which is purportedly pegged to the US dollar at a 1:1 ratio by the Tether Corporation. While the corporation’s original ‘white paper’ stated that Tethers would be fully backed by US dollars, this is no longer the case. But Tether still trades at very close to $1 on secondary markets.

Why do people use Tether rather than the US dollar? Buying or selling cryptocurrency with traditional money, especially in large quantities, can incur considerable compliance costs. By holding Tethers rather than US dollars, frequent crypto traders do not have to incur these costs as often. Major financial institutions have often been reluctant to deal with the Tether Corporation because of the potential for Tether to facilitate money laundering, and the corporation is currently under investigation by the state of New York.

Another well-known stablecoin is Facebook’s Libra, which has recently been rebranded as Diem. This is a proposal for a virtual currency, run by a conglomerate of firms led by Facebook, which would be pegged to a basket of major currencies. As of December 2020, this stablecoin has not yet been launched, and the response from regulators has been so hostile that it may never be launched. Steven Mnuchin, US Secretary of the Treasury, responded to the initial white paper with the comment ‘I hate everything about this’, and Libra was later criticised in a tweet by President Trump.

Partly in response to the perceived threat posed by private currencies, central banks around the world have begun to research ways in which these technologies could be used to create state-controlled digital currencies.

What are central bank digital currencies?

A central bank digital currency (or CBDC) is a form of electronic money issued by a central bank. Existing national currencies can be traded electronically, so what is the benefit of a CBDC? This varies from one proposal to the next: it might be to allow the public to access central bank lending or to facilitate a move to a smoother payments system. A more sinister possibility is that a CBDC could allow an authoritarian government to record all transactions on a blockchain for the purposes of law enforcement.

To date, only a small number of CBDC schemes have been attempted. Finland’s ‘Avant’ digital currency was rendered obsolete by improvements to the debit card system in the early 2000s. Uruguay has issued ‘e-Pesos’ in a successful trial of the concept of a CBDC, and is currently considering whether to continue the project on a larger scale. The largest project in development is the People’s Bank of China’s ‘digital cash/electronic payments’ project, which is intended partly to replace physical cash and has been piloted in several regions.

While a successful CBDC would lead to economic gains from a more efficient payments system, a botched implementation could pose risks to financial stability (Kumhof and Noone, 2018). For this reason, central banks globally are proceeding with caution. As of January 2019, only a small number of central banks in countries with atypical monetary circumstances had plans to implement a CBDC in the short to medium term (Barontini and Holden, 2019).

What else do we need to know?

A common mistake in media coverage of Bitcoin is to assume that a change in its price is indicative of a change in the long-term probability of its adoption. But Bitcoin market movements are rarely related to economic fundamentals, for two reasons:

- First, prices are highly sensitive to the issuance of additional unbacked Tethers (Griffin and Shams, 2020).

- Second, the ownership of Bitcoin is highly concentrated: by one estimate, 2% of accounts control 95% of Bitcoin. As a result, many significant price changes are simply the result of large trades by a single investor (Shen et al, 2019).

Where can I find out more?

- Attack of the 50 foot blockchain: David Gerard details the technology behind Bitcoin and chronicles its history up to 2017 from a highly sceptical perspective.

- Sex, drugs, and Bitcoin: how much illegal activity is financed through cryptocurrencies?: A paper in a leading finance journal by Sean Foley, Jonathan Karlsen and T?lis Putni?š, which attempts to quantify the extent to which Bitcoin is used for illegal purposes.

- Tether: the story so far: Patrick McKenzie of Stripe describes the background, development and growth of Tether, as well as its continuing legal difficulties and effect on the market for cryptocurrencies.

- Stablecoins: risks, potential and regulation: A recent Bank for International Settlements paper by Douglas Arner, Raphael Auer and Jon Frost, which explains the risks and opportunities associated with stablecoins.

- Central bank digital currencies: drivers, approaches and technologies: A VoxEU piece by Raphael Auer, Giulio Cornelli and Jon Frost, which outlines the status of CBDC projects and explains the technical choices involved in their creation.

Who are the experts on this question?

- Frances Coppola

- John M. Griffin

- John Paul Koning

- Amin Shams

- Andrew Urquhart

Author: William Quinn, Queen’s University Belfast

The post Are Bitcoin and other digital currencies the future of money? appeared first on Economics Observatory.

]]>The post What are the effects of lockdown and recession on domestic violence? appeared first on Economics Observatory.

]]>How much has domestic violence increased in recent months?

Consider early statistics for the UK. In the first month after the initiation of lockdown on 23 March, the rate of homicide of women was more than twice the average of two women a week, and the highest rate in the last 11 years (The Guardian, 2020). At the same time, 80% of women’s frontline support services reported a reduced service because of less face-to-face contact, staff sickness and technical issues, including insufficient laptops to enable working from home (The Guardian, 2020).

The media in many countries have highlighted an increase in calls to domestic violence helplines since the onset of the pandemic. As domestic violence tends to exhibit seasonal variation, researchers have compared 2020 indicators with indicators for the same week or month in the preceding year or years.

For example, a study of calls to the Metropolitan Police Service in London shows an 11.4% increase in calls related to domestic abuse relative to the same weeks in the preceding year (Ivandic and Kirchmaier, 2020). The increase is entirely driven by calls from third parties (such as neighbours and other family members) rather than victims. This may in part be because neighbours are more likely to be at home, but it also squares with reports from around the world that women may find it harder to find the space to make a call when they are locked in with the perpetrator.

Data on actual cases (rather than calls) reveal an 8.5% increase in violence against current partners as well as a decrease of 9.4% in violence against ex-partners. This fits with mobility restrictions having made it harder to commit crimes outside the home.

Using variation in lockdown across the Indian districts, Ravindran and Shah (2020) show that domestic violence complaints increased more in districts with the strictest rules. But rape and sexual assault complaints fell, which is consistent with decreased mobility of women in public spaces.

Attitudes toward domestic violence play an important role in reporting. A study using Italian data finds a doubling of calls to the domestic violence helpline following the introduction of an anti-abuse campaign that encouraged reporting (Colagrossi et al, 2020). The analysis also shows smaller increases in areas with higher baseline rates of gender inequality, which the researchers attribute to differences in reporting.

Similarly, a study using data from 15 large US cities shows that the pandemic was associated with a 10.2% increase in domestic violence calls (Leslie and Wilson, 2020). The timing of the increase coincides with people spending more time at home, as evident from GPS tracking of mobile phones and data on seated restaurant customers. The increase in reported incidents is evident across demographic groups, and it appears to be driven by households without a history of domestic violence, both of which undermine the relevance of ‘structural’ causes.

Although, in general, domestic violence tends to spike on weekends, the pandemic-related increases in these US cities are most evident on weekdays, which is consistent with individuals being at home who in previous years would have been at work. But the evidence is still ambiguous. Another US study, of eight cities, finds no evidence that serious domestic assaults increased during lockdown (Ashby, 2020); and a study in Queensland finds no increase in breaches of domestic violence orders (Payne and Morgan, 2020).

Further research that identifies mechanisms and isolates incidence from reporting is needed. The studies of Italy and India cited above indicate that reporting is influenced by gender norms. It may also be influenced by unemployment (Bhalotra et al, 2020).

In the early weeks of the Covid-19 crisis, reporting was made harder as a result of support services being under-staffed, but in response to reports of rising domestic abuse, many countries have introduced special measures to encourage reporting. A careful analysis of the surge in domestic violence in the wake of the pandemic requires adjusting for both behavioural and policy-driven changes in reporting.

What does research on domestic violence tell us about its causes?

At first glance, an increase in reports of domestic violence since the onset of Covid-19 is consistent with what we know about the causes of domestic violence. Covid-19 has led to job loss (Adams-Prassl et al, 2020; Hupkau and Petrongolo, 2020; Alon et al, 2020), a deterioration in mental health associated with economic uncertainty and reduced contact with friends and support networks (Banks and Xu, 2020; Etheridge and Spantig, 2020). It has also led to the immediate family being forced to spend more time together at home.

Related question: How might social isolation affect people's wellbeing during the pandemic?

In the rest of this section, we consider the predictive power of alternative approaches to understanding the drivers of domestic violence.

The lens of household bargaining

Research for the UK, which leverages differences in local area unemployment rates for men and women in a period that included the 2008/09 recession, shows that increases in men’s unemployment lower domestic violence, while increases in women’s unemployment raise it (Anderberg et al, 2016). A study using data on changes in the wages of women relative to men finds a similar result in the United States (Aizer, 2010).

These patterns can be rationalised with reference to economic analysis of household bargaining in which the power balance within the couple is influenced by their ‘outside options’. Deterioration of men’s earnings potential will attenuate their power (because it weakens their options outside the current partnership), and this will tend to tame them into less violent behaviour. Similarly, if the woman’s outside options deteriorate, she may be more likely to tolerate violence than if she could walk away with self-sufficiency from the partnership.

Women’s jobs have suffered more in the Covid-19 crisis than men’s jobs because, unlike in previous recessions, women happen to be over-represented in the hardest hit sectors (Adams-Prassl et al, 2020; Hupkau and Petrongolo, 2020; Harkness, 2020). This may explain the observed increase in domestic violence.

Related question: How will the response to coronavirus affect gender equality?

Male backlash and instrumental control

Since the shadow pandemic of domestic violence is global in nature, it is important to recognise that the behavioural patterns evident in the UK and the United States may not hold everywhere.

Alternative (sociological) analysis of ‘male backlash’ (Macmillan and Gartner, 1999) reverses the predictions of the household bargaining model. If male identity is closely tied to a breadwinner norm, men’s job loss will tend to prime male identity, create stress and trigger domestic violence. Alternatively, if men seek to control their partners by sabotaging their economic activity or if they seek to usurp resources in the hands of women (Anderberg and Rainer, 2011; Bloch and Rao 2002), then a decline in women’s earnings may lead to lower domestic violence.

Consistent with this is evidence that an improvement in the financial circumstances of women leads to higher domestic violence (Heath, 2014; Bhalotra et al, 2019; Tur-Prats, 2019; Estefan, 2019; Kotsadam and Villanger, 2020; Carr and Packham 2020).

Overall, domestic violence appears to be sensitive to how the pandemic alters women’s financial position relative to that of men. But the direction of the effect appears to depend on underlying gender equality, conditioned by social norms and women’s access to financial independence.

Household income losses

The models of behaviour discussed so far focus on the relative or absolute earnings of the woman. Another possibility is that violence is triggered by a decline in household income (Bhalotra et al, 2020).

Previous research establishes that job loss leads to heightened stress (Black et al, 2015; Schaller and Stevens 2015). It seems plausible that income constraints contribute to stress, which lowers the bar for conflict. For example, couples may need to renegotiate how their more limited resources are spent.

The Covid-19 surge in domestic violence is consistent with this explanation as many households have suffered a significant fall in income, and additional stress from uncertainty over the duration and extent of the decline.

Cash transfers

If the total loss in household income is a driver of domestic abuse, then welfare payments may mitigate. It turns out that this depends first, on who receives the payments, and second, whether payments have unintended behavioural effects. Experiments conducted in Kenya (Haushofer et al, 2019) and Mali (Heath et al, 2020) show that cash transfers to men lead to lower rates of physical violence.

Results from studies of cash transfers to women are more mixed. In some cases, there is a decline in violence (Hidrobo et al, 2016; Heath et al, 2020), but in other cases, there is an increase that appears to arise from men using violence to extract resources from the woman (Angelucci, 2008; Carr and Packham, 2020).

Unemployment benefits appear not to mitigate the problem, which is because they lead to longer unemployment duration. While the cash benefits are effective in easing constraints on household finances, this is offset by longer unemployment duration, which increases ‘exposure’ or opportunities for violence (Bhalotra et al, 2020).

Time spent at home

The exposure model, emerging from criminology, emphasises the role of exposure or the time that couples spend together (Dugan et al, 2003). It is consistent with the stylised fact that domestic violence tends to escalate during national holidays, weekends and nights (Vazquez et al, 2005) and during periods of bad weather (RAINN in the United States) because in these cases families are at home together for longer.

Increases in unemployment or unemployment duration lead to more time at home. Lockdown has reinforced this by forcing families to be together for long periods of time. Media coverage of the Covid-19 spike in domestic violence in several countries refers to women being ‘stuck at home’, unable to ‘escape’ to relatives, or to call on their social network. For example, ‘It is thought that [domestic violence] cases have increased by 20% during the lockdown, as many people are trapped at home with their abuser’ (BBC News, 2020).

There appear to be no experimental estimates of the causal effects of exposure on domestic violence. But the fact that lockdown has forced many families on full pay to spend more time together at home provides a unique opportunity to investigate this.

What are the policy options for tackling domestic violence?

The scale of the problem was already large before Covid-19. Recent estimates from a major multi-country study reveal that, on average, one in three women report that they have experienced intimate partner violence at some point in their lives (Garcia-Moreno et al, 2006).

The focus of the discussion so far has been on intimate partner violence, but this often coincides with child abuse. US data indicate that about a quarter of all children subject to maltreatment at home in 2015 lived in households with reports of physical intimate partner violence (US Department of Health and Human Services, 2017). This strengthens the case for policy interventions.

Prior to Covid-19, policies addressing domestic violence have included women’s shelters, counselling, preventive orders, training programmes for perpetrators and skills training or job opportunities for women. Policy responses to the spike in domestic violence during the Covid-19 pandemic have taken the form of additional government funding, measures to encourage reporting, and measures that facilitate women moving out to a safer space.

For example, in the UK and elsewhere, hotels have been asked to open their emptied rooms to women seeking refuge, and women who need to leave abusive partners are now allowed to travel on trains without purchasing a ticket. Measures to facilitate reporting include allowing women to use a code on their phones when it is not safe to speak (the ‘silent solution’), to send a quiet WhatsApp message, or to report abuse to pharmacies, post offices, grocery stores or other routine contact points.

These are all useful and timely measures, but much less attention has been paid by policy-makers to implementing measures to address the actual incidence of domestic violence. Policies that compensate individuals for the loss in earnings or employment may indirectly act to lower domestic violence, but going forward, more fundamental research is needed to understand how best to design preventive measures. This requires an understanding of how people respond to incentives and constraints.

Over and above identifying causes, policy in this domain must be sensitive in designing solutions that can accommodate the privacy of the individuals involved, consider the children in the household, and recognise the fact that some women victims may want redress but may not want their partners incarcerated or fined, while other women may seek ways to leave the marital home.

Where can I find out more?

Covid-19 and ending violence against women and girls: Policy brief from UN Women.

Domestic abuse in times of quarantine: Crime economists Ria Ivandic and Tom Kirchmaier look at data on domestic abuse calls to the police in London.

WHO multi-country study on women’s health and domestic violence against women: 2006 report by the World Health Organization.

The impact of COVID-19 on women and children experiencing domestic abuse, and the life-saving services that support them: Women’s Aid.

Layoff, benefits and domestic violence: first draft study by Sonia Bhalotra, Diogo Britto, Paolo Pinotti and Breno Sampaio – available on request by email.

Who are experts on this question?

- Sonia Bhalotra

- Anna Aizer

- Dan Anderberg

- Manuela Angelucci

- Jillian Carr

- Claudio Deiana

- Andrea Garcia

- Ludovica Giua

- Johannes Haushofer

- Rachel Heath

- Melissa Hidrobo

- Andreas Kotsadam

- Emily Leslie

- Analisa Packham

- Manisha Shah

- Ana Tur-Prats

- Helmut Rainer

- Riley Wilson

Author: Sonia Bhalotra

Photo from Adobe Stock

The post What are the effects of lockdown and recession on domestic violence? appeared first on Economics Observatory.

]]>The post Is hate crime rising during the Covid-19 crisis? appeared first on Economics Observatory.

]]>Coverage of threatening events in social and traditional media plays an important role in this link. The highly threatening nature of Covid-19 itself, as well as the lasting negative economic, political and social consequences of the current response to the pandemic, are likely to increase xenophobic and racist attitudes and associated hate crimes and incidents in the short term, with potentially long-term consequences too.

It is important to keep in mind that while we discuss general patterns in racist and anti-immigrant attitudes and behaviour of the dominant group towards ethnic, racial, religious and national minorities, there is variation over time and across groups (Ford 2008; Poynting and Mason, 2007).

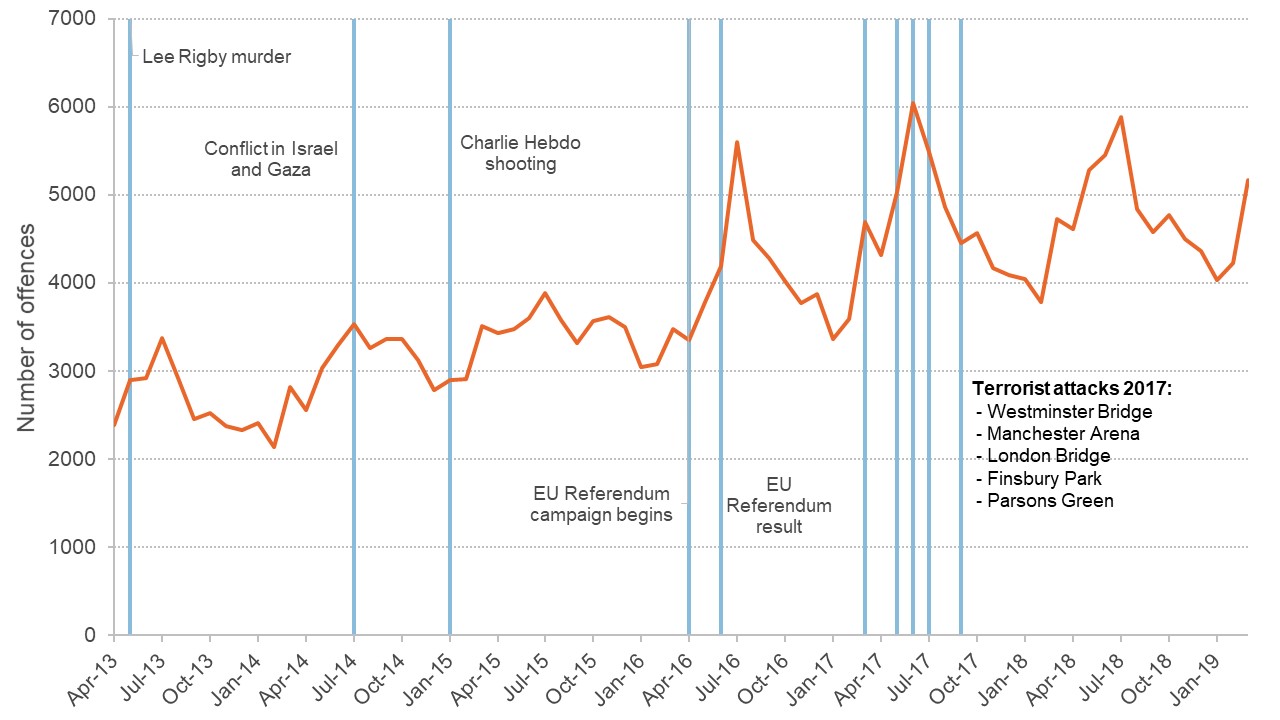

As Figure 1 shows, hate crime reports have been generally increasing over the past seven years. Some threatening events, such as the referendum result in June 2016 and the terrorist attacks of 2017, match with sharp spikes in hate crime reports; but other events, such as the Charlie Hebdo shooting in Paris in 2015, do not.

It is also difficult to separate the effect of threatening events from unrelated trends or events that may influence hate crime reporting. Recent social science research that measures this relationship in more robust ways is summarised below.

Figure 1: Number of racially or religiously aggravated offences recorded by the police by month

Source: Home Office, 2019

What does research in economics and sociology tell us about the association between threatening events and racist attitudes and behaviour?

Theories of social or group-based identities, developed by social psychologists, have long established the existence of favourable attitudes and behaviour towards in-group members and discriminatory practices towards out-group members (Tajfel, 1981).

Sociologists (such as Bobo, 1999) and economists (Akerlof and Kranton, 2000) discuss how these individual preferences, produced and strengthened by group-based identities, operate in the aggregate to shape ethnic inequality in life chances, as well as perpetration of and exposure to discriminatory acts. In times of increased competition for scarce resources, as well as opportunities and events that heighten the salience of social identities, these prejudicial attitudes and behaviour may strengthen.

Fear of infectious disease is also associated with irrational economic and social responses (Smith, 2006; O’Shea et al, 2020, on US data). Research finds that infectious disease outbreaks, such as the Ebola crisis in 2014, led to an increase in racist and xenophobic attitudes (Broom and Broom, 2017, on Australian data; Kim et al, 2016, on US data). The link between increasing saliency of infectious disease and anti-immigrant attitudes appears to hold even in experimental settings (Bartos et al, 2020, on data from the Czech Republic).

Economic downturns may also be associated with an increase in discrimination against ethnic and religious minorities: research finds substantial increases in both self-reported racial prejudice, and wage and employment gaps between majority and minority members during periods of higher unemployment (Khattab and Johnston, 2013, on UK data; Kingston et al, 2015, on data from Ireland; Johnston and Lordan, 2016, on UK data).

Related question: What will be the impact of Covid-19 on public attitudes to immigration?

Information channels play an important role. Racist and anti-immigrant media portrayals of threatening events are associated with increases in hate crime and xenophobic and racist behaviour (Adena et al, 2015, on data from Germany). This association can be intensified where such portrayals are spread via social media (for a review, see Zhuravskaya et al, 2020).

Research suggests that threatening events involving one out-group can have wider impact, increasing xenophobia and racist attitudes and behaviours more generally. For example, during the Ebola outbreak, which originated in West Africa, researchers found increases in xenophobic attitudes both directly towards West Africans, but also towards undocumented immigrants, the majority of whom were not of African descent (Kim et al, 2016, on US data).

Such ‘spillover’ effects have also been shown to relate to media portrayals. For example, researchers have demonstrated that negative media portrayals linking Islamophobia and immigration following the 9/11 attacks (Romero and Zarrugh, 2018, on US data) resulted in longer prison sentences for minority group members perceived as immigrants, Hispanic defendants, although not for minority group members perceived as native-born, black defendants (McConnell and Rasul, 2020, on US data).

Spikes in hostile attitudes and hate crimes against ethnic minorities and immigrants are commonly observed following terrorist attacks, highly publicised inter-racial crimes and contentious political events such as Brexit (Home Office, 2019, on the UK; Jäckle and König, 2018, on Germany; King and Sutton, 2013, on the United States; Legewie, 2013, on European data; Disha et al, 2011, on the United States; Poynting and Mason, 2007, on the UK and Australia).

It is less known how long such increases in hostility endure. For example, in the case of Brexit, anti-immigrant attitudes have already declined to below pre-Brexit levels (Schwartz et al, 2020).

What new work is emerging on changes in xenophobic and racist behaviour and attitudes due to the Covid-19 crisis specifically?

The emerging evidence shows that the Covid-19 pandemic is associated with an increase in hate crime reporting, especially against Chinese and East Asian minorities. Research also shows that the crisis may increase hostility towards out-group members more generally. Social media use, especially exposure to far right-wing propaganda, may exacerbate this effect.

In the UK, the United States and Canada, police data and reports from non-governmental reporting organisations reveal dramatic increases in reporting of hate crime against East Asian minorities (Tessler et al, 2020; BBC News, 2020; Vancouver Sun, 2020). Police forces across the UK received 267 incidents of hate crime reported by Chinese minorities in the UK during the first quarter of 2020, compared with 375 incidents during the entire year in 2019 (Sky News, 2020).

New research using a money allocation experiment of a nationally representative sample in the Czech Republic under lockdown finds that increasing the saliency of Covid-19 increased hostility towards immigrants, such that the experimental subjects allocated less money to non-Czech participants when Covid-19 was made salient (Bartos et al, 2020).

There is emerging evidence that increases in out-group hostility are linked to media portrayals of Covid-19. Web analysis finds increases in anti-Chinese language both on fringe and mainstream (Twitter) websites (Schild et al, 2020). Survey research from the United States establishes a link between social media use during the Covid-19 pandemic and xenophobic attitudes specifically towards Chinese minorities (Croucher et al, 2020).

Who is likely to experience an increase in the risk of racist attacks and harassment due to Covid-19?

There is emerging evidence (see also above) that East Asian minorities are most at risk of racist attacks. For example, disproportionately high declines in mental health during the Covid-19 crisis experienced by Canadian residents of East Asian origin might be partially explained by experiences of discrimination (Wu et al, 2020).

Research also suggests spillovers of Covid-19-related hostility to immigrants more generally, as evidenced in experimental work from the Czech Republic (Bartos et al, 2020) as well as the anti-immigrant (as well as anti-Chinese) rhetoric employed by the US president and recent immigration restrictions introduced in the United States.

There is evidence showing that minorities living in areas with a higher proportion of their own ethnic group have a lower risk of experiencing ethnic and racial harassment (Nandi and Luthra, 2016; Disha et al, 2011, Becares et al, 2009; Dustman et al, 2004).

Evidence is mixed on whether this is because minorities are less likely to come into contact with majority group members, because majority group members living in such areas are less hostile or because the potential sanctions against ethnic and racial harassment is higher in areas of higher minority concentration.

Economically advantaged minorities are more likely to report ethnic and racial harassment, which could be due to greater confidence and ability to identify incidents as being due to racism and discrimination, or due to greater contact with majority group members (Dixon et al, 2010; Steinmann, 2019; Verkuyten, 2016).

UK evidence shows that women are less likely to report experiencing ethnic and racial harassment, but more likely to find public places unsafe and avoid them (Nandi and Luthra, 2016).

How reliable is the evidence?

The reliability of this data-based evidence depends on:

- The accuracy of reporting of attitudes by the dominant or majority group towards ethnic, racial, religious and national minorities.

- The accuracy of reporting of experiences of discrimination and harassment by ethnic, racial, religious and national minorities.

- The robustness of the statistical methods used and the representativeness of the sample.

A vast body of research in survey methodology has established the role of social desirability bias in survey reporting, where survey respondents have a tendency to report in accordance with social norms, which is heightened in the presence of an interviewer (Lavrakas, 2008; deLeeuw, 2005; Tourangeau et al, 2000). As a result, there may be under-reporting of racist and anti-immigrant attitudes in societies where such attitudes are considered to be unacceptable.

In surveys, self-reporting on experiences of discrimination and harassment is hindered by the inability to identify such acts (for example, because the person is new to the region and not familiar with racial slurs, etc. or because such incidents are so common that they have become normalised) and lack of confidence in reporting.

In the case of reporting to organisations and institutions including the police, not only are these barriers more difficult but there is an additional hurdle: lack of information on how and where to report. It should also be noted that by definition, only those incidents that qualify as crimes are counted as hate crimes: the others are recorded as hate incidents.

The reliability of survey data-based evidence depends on how well the population is represented in the sample from which the survey data are collected, and the statistical methods used to produce the estimates. Weighted estimates based on surveys of samples drawn from a specific population (such as young people or specific minority groups) will provide estimates that are only generalisable to that population.

Finally, it may also be difficult to establish the existence and strength of the causal link between a threatening event and changes in racist and anti-immigrant attitudes and discriminatory behaviour due to confounders.

For example, a threatening event may coincide with increases in immigration or deterioration in inter-group relations: it is therefore difficult to determine whether any increase in racist attitudes is due to the event or related trends in attitudes. In the case of the current pandemic, this may not be a problem as it is an unanticipated event that could not have been the result of racist and xenophobic attitudes or behaviour.

Still unknown: the effects of Black Lives Matter and the lifting of lockdown

What is different about the current crisis compared with threatening events in the past is the shutdown following the outbreak. So while hate crimes may show a drop during lockdown, they may have spiked in online spaces where social interaction has shifted. The limited evidence that was available before lockdown in the United States and the UK (Tessler et al, 2020 and Sky News 2020) indicates that there is a possibility of rise in hate crimes against residents of Chinese and East Asian origin.

But something else happened during the Covid-19 crisis: the differential impact of the disease on minority communities – due to their concentration in key worker and healthcare occupations, and their higher rates of infection and death – was widely reported in the UK and the United States (PHE report, 2020; Platt and Warwick, 2020; Meer et al, 2020).

Related question: How is coronavirus affecting inequalities across ethnic groups?

This work also highlights the existing economic vulnerability of racial and ethnic minorities (Platt, 2020), and the role of existing racist structures and discriminatory practices (Becares and Nazroo, 2020; Guardian, 2020), which were widely discussed.

This media attention was immediately followed by the unprecedented rise and spread of the Black Lives Matter (BLM) movement across the United States and the world following the death of George Floyd, an unarmed black man in the custody of the Minneapolis police. Protests around this movement are continuing in the UK at the time of writing with responses from both private and public institutions as well as policy-makers.

Given the potentially countervailing events of the Covid-19 crisis, the decrease in in-person interaction during lockdown, and the heightened awareness of discrimination and inequality exemplified by Black Lives Matter, it will be difficult for researchers to unpick the causes of changes in hate crime and discriminatory attitudes arising during this time.

Where can I find out more?

Discover Society: the Covid-19 Chronicles: a selection of articles on the relationship between Covid-19, the experiences of minorities and anti-racist social movements.

Black Lives Matter: the official webpage of the movement.

Guardian coverage of the Black Lives Matter movement.

The Equality and Human Rights Commission: information on hate crimes and how to report them.

Hope Not Hate: coverage of coronavirus and hate crime.

Research projects

The International Network for Hate Studies is a repository of hate crime studies.

The Centre for Hate Studies at Leicester.

The Sussex Hate Crime Project (2013-18) examined the indirect effects of hate crimes.

The prevalence and persistence of ethnic and racial harassment and its impact on health: a longitudinal analysis project (2016-17).

Where can I report hate crime?

https://www.gov.uk/report-hate-crime

Who are experts on this question?

- Dominic Abrams

- Laia Becares

- Benjamin Bowling

- Rupert Browne

- Neil Chakraborti

- Mónica Moreno Figueroa

- Miles Hewstone

- Renee Luthra

- Alita Nandi

- James Nazroo

- Lucinda Platt

- Imran Rasul

- Satnam Virdee

- Mark Walters

Authors: Renee Luthra and Alita Nandi

The post Is hate crime rising during the Covid-19 crisis? appeared first on Economics Observatory.

]]>The post Do we make informed decisions when sharing our personal data? appeared first on Economics Observatory.

]]>People have concerns about the protection of their personal data, or they might not see the full costs and benefits. If a sizeable share of society is unwilling or unable to provide their data, this would call into question the viability of large-scale data-based policy measures. There is also an issue with setting a precedent for surveillance once the pandemic is over.